05/03/2022

Design Histories Overview

An introduction to the curriculum and a note on the subject of history

The great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do.James Baldwin

The Past Is Not Behind Us

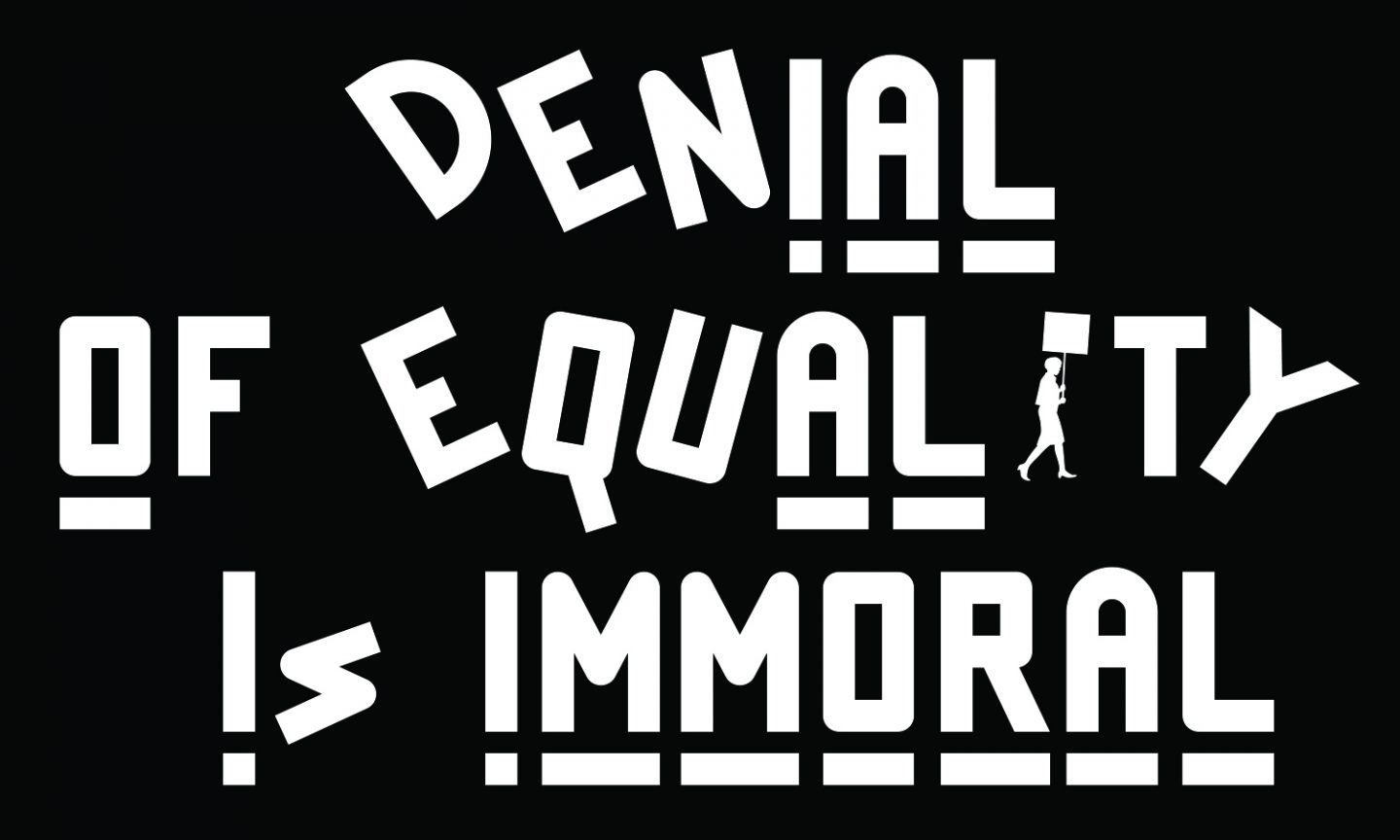

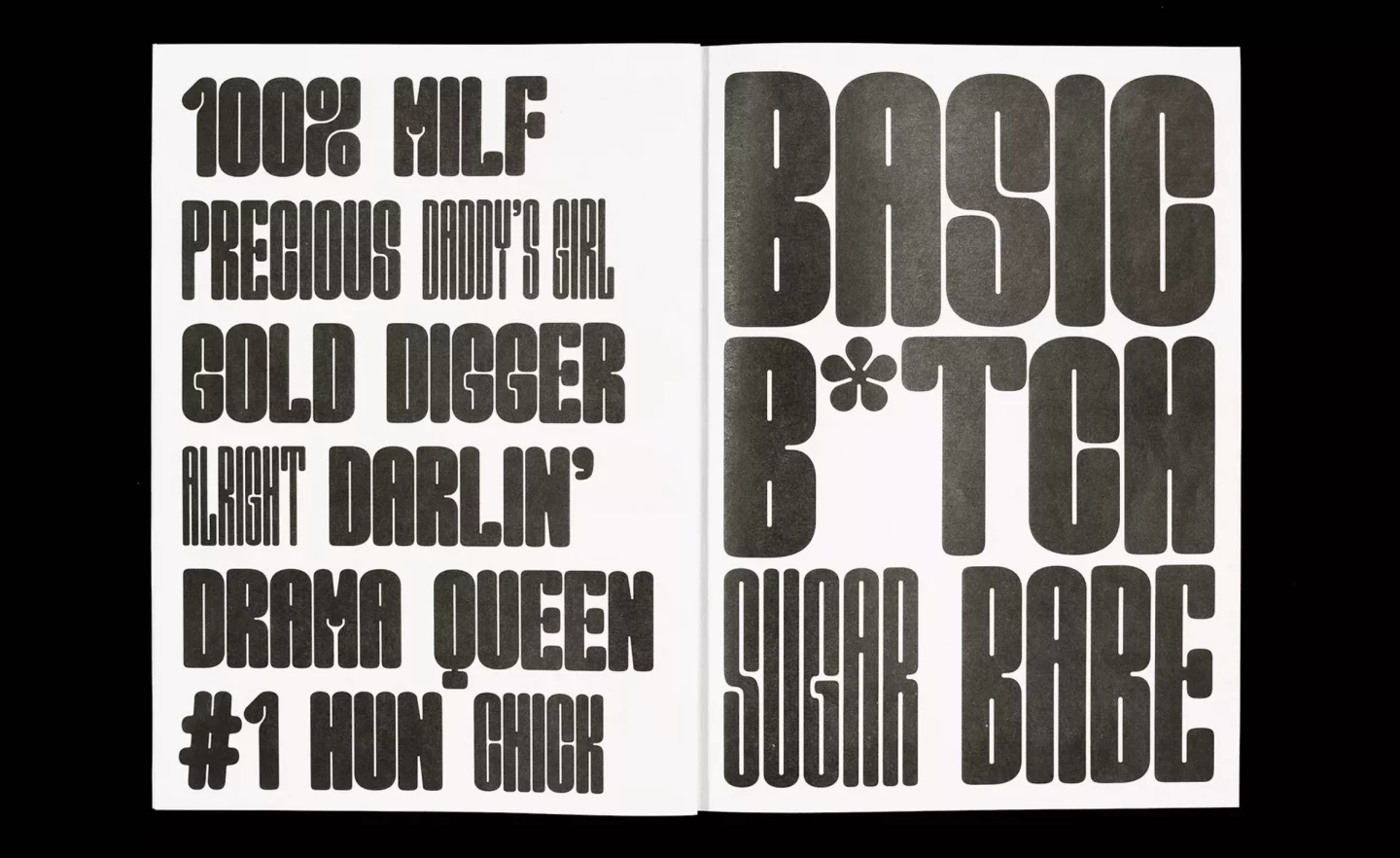

The function of visual communication is inherently social and political.

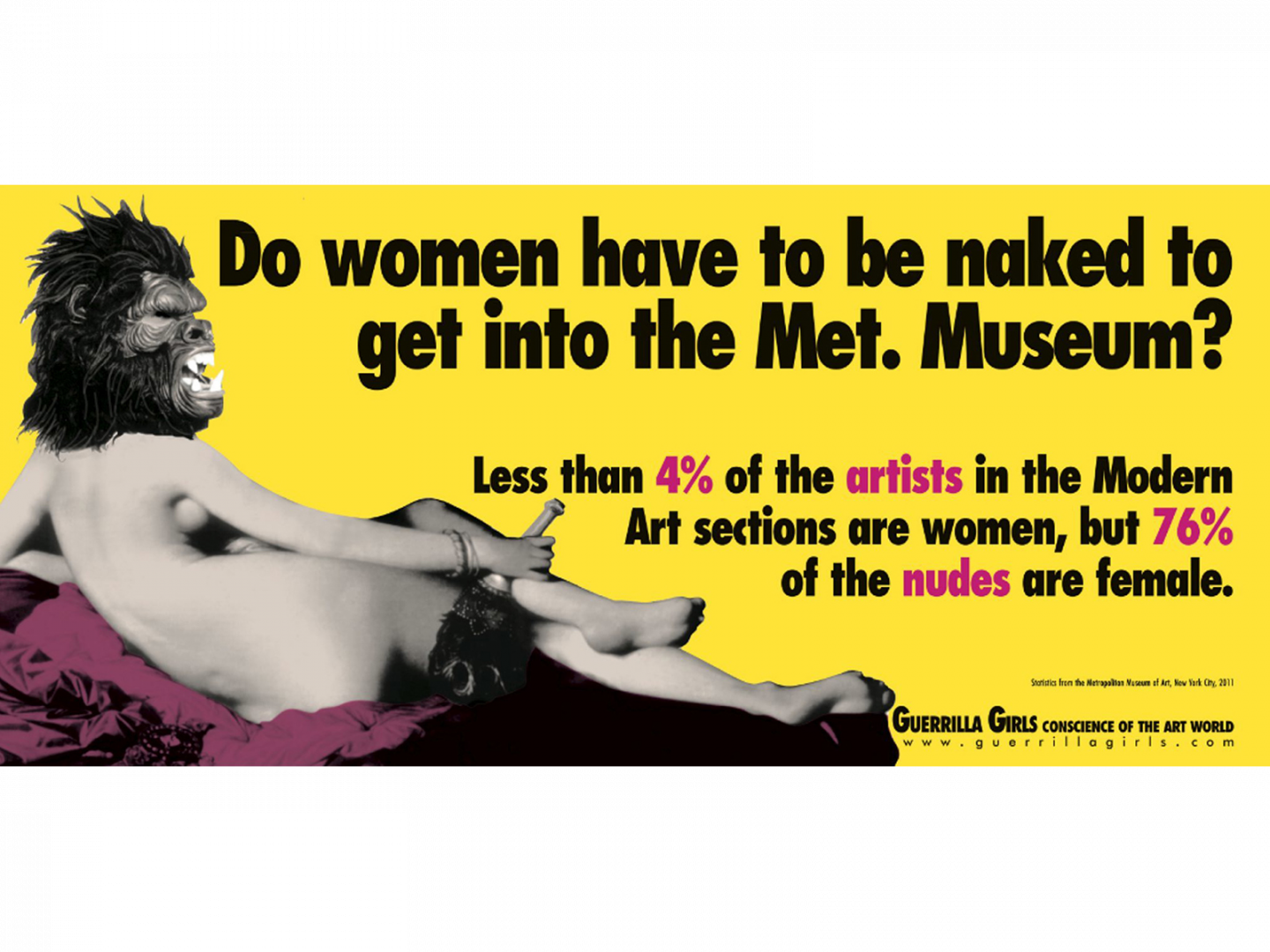

A designer’s contributions, when disseminated through standard channels of media, have the potential to reach considerable audiences and produce significant social impact. Works of graphic design are most often commissioned by dominant entities—businesses, corporations, cultural institutions— to transmit specific values and ideas crafted to generate economic gain and cultural influence. En masse, these works perpetuate the systems and structures that shape our collective experience.

Whether an individual designer is conscious of the consequences of their output is irrelevant, the expression of visual concepts within the public sphere, when repeated over platforms of marketing and advertising, create thought, manipulate perspectives, and, in turn, alter reality.

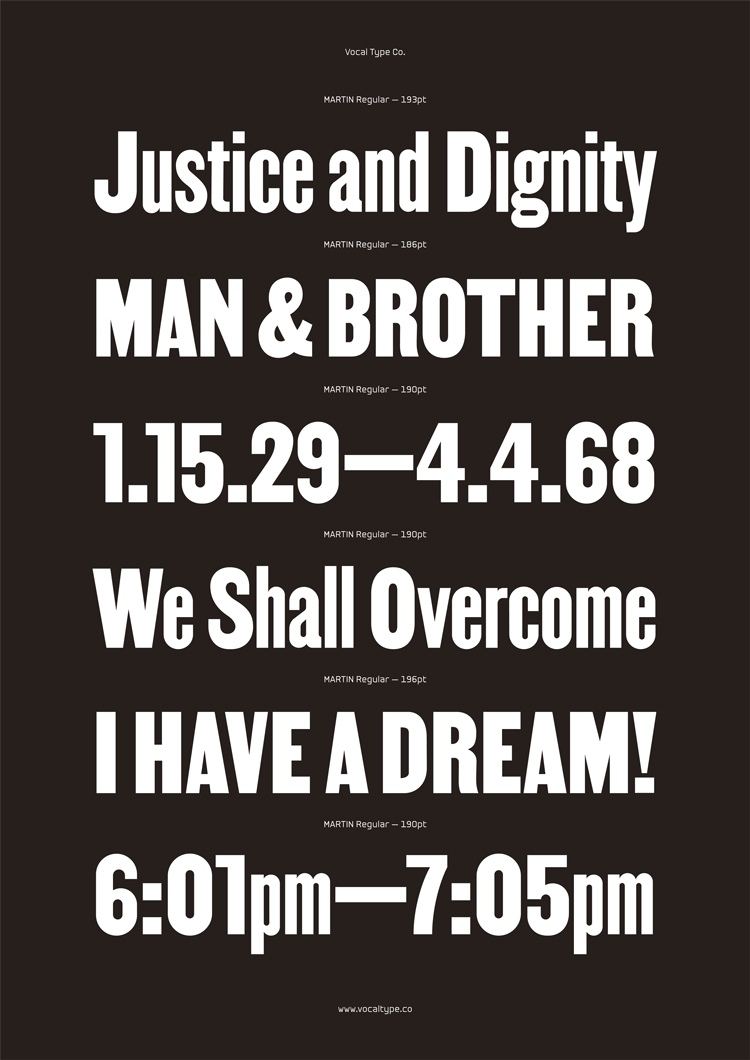

Because of this transformative capacity latent in the act of design, it is crucial that designers be informed, accountable and intentional in their practice. This entails, among other things, developing a general knowledge of history—a basic comprehension of the movements and events that have formed the framework of contemporary society.

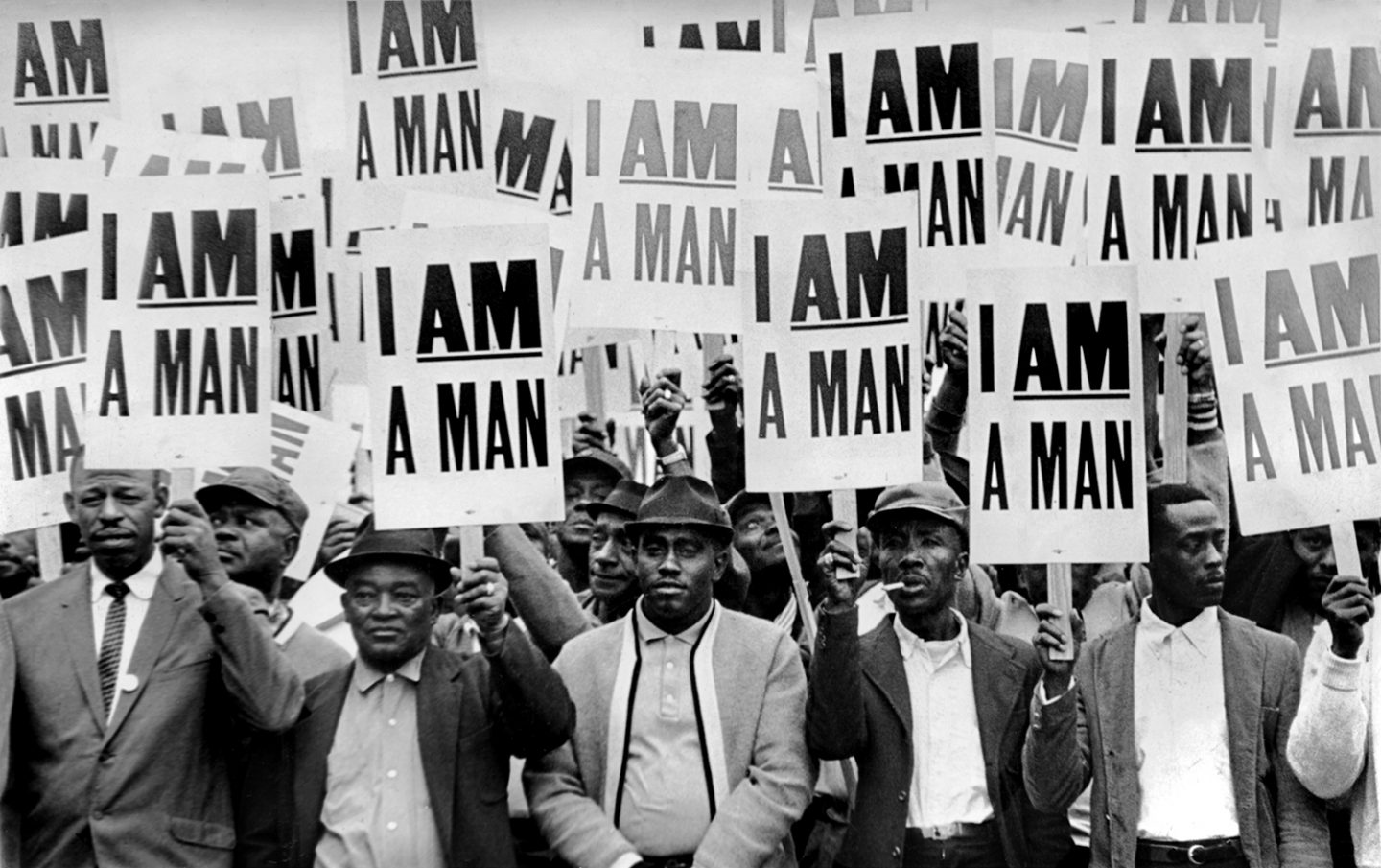

These past milestones—achievements, ideas, innovations, challenges, transgressions, victories, and defeats— once assimilated into our common mythology, serve to legitimize what is culturally agreed upon to be real and true. They determine who and what is acknowledged, valued, celebrated, preserved, condemned, and forgotten.

In other words, the past is not behind us.

The approach of Design Histories is centered on critically examining our collective canon of thought within the sphere of design and beyond. There will be a particular focus on socio- economic systems, technologies, and cultural conventions—all of which contribute to the visual character of a particular design movement or period. We will interrogate the correlation between aesthetics, cultural perceptions of value, and underlying structures of political and economic power.

During the course of the semester, we will investigate the past to more fully comprehend its relationship to the present and future. Time is not linear; existence is not singular. The objective of the class is not to promote or legitimize any one single experience, methodology, movement, or body of work, rather, the intent is to create a space to question our current experiences for the sake of better understanding how we connect to the many versions of the past, present, and future that exist.