03/04/2022

The Catalyst of Industry

The Industrial Revolution generates new innovations and creative perspectives

You can’t have an industrial revolution, you can’t have democracies, you can’t have populations who can govern themselves until you have literacy. The printing press simply unlocked literacy.Howard Rheingold

The industrial revolution that began in England in 1760 was the culmination of numerous developments over the span of hundreds of years. The Chinese innovations which first came into the European purview during the 12th and 13th centuries—printing, paper making, gunpowder, and the compass— set the groundwork for both Gutenberg’s printing press and the era of European colonialism that would begin in the 1400’s. In turn, these conquest, along with the explosion of printing throughout Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries, would create an exchange of beliefs and ideas which would both perpetuate and disseminate the emerging viewpoints of the Renaissance and the Age of Enlightenment. Each milestone built on the one that came before. Every new invention served as an inspiration for the next. This chain reaction of advancement and progress would ultimately position Europe as a central power within an expanding network of industry and commerce. The resulting system of early global capitalism would, by the twentieth century, establish the European perspective as the dominant cultural viewpoint that would define the modern world.

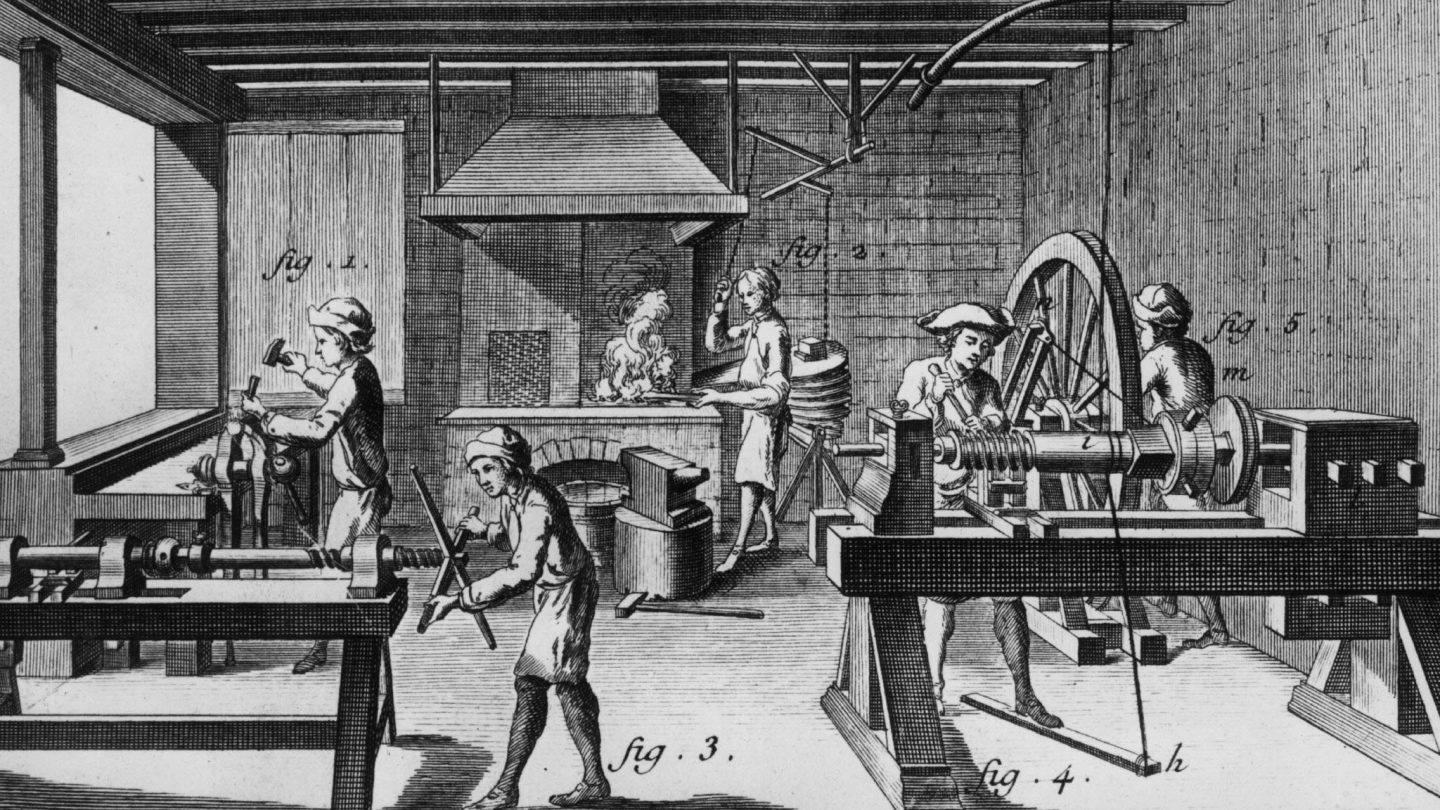

The impacts of the industrial revolution both transformed socio-economic structures and further expanded the inequities that were inherent in the preceding feudal system. The new industries that emerged required proximity of labor. Great numbers of the population moved from rural location to urban centers to work in factories. Cities became centers of production, manufacturing, commerce, and culture.

Industrial innovation increased production tremendously—generating more wealth and power for those who were at the helm of these industries. Class disparity increased as a result of the industrial revolution. Because the systems of production and manufacturing were new, there was no regulation to counteract the negative circumstances they would generate. There were no protocols in place protecting and advocating for those who would be exploited by these new systems. Working conditions for the laborers of the industrial revolution were horrendous. There are countless accounts of dangerous and oppressive working conditions. In the quest for cheap labor and optimum productivity, factories owners implemented a variety of inhumane strategies from employing children to locking workers indoors and forcing them to work through the night.

There were also positive aspects to the industrial revolution of course. Mechanization completely transformed production methods making them faster, easier, more efficient, and more profitable. The economic advantages of these new methods would eventually trickle down. By the mid 1800’s, a middle class began to emerge which would offset the extreme divide between rich and poor that had characterized the first century of industrialization. This new middle class would become a primary audience for the goods and services of the Victorian era.

New innovations in printing significantly increased public access to ideas and information. Developments like, the steam powered press, the Linotype machine, chromolithography, and photography would result in a wider variety of printed matter at more affordable prices. These new production methods were faster and cheaper and generated more printed goods than any previous time. The amount of books magazine, and periodicals available for public consumption increased tenfold during the 1800’s.

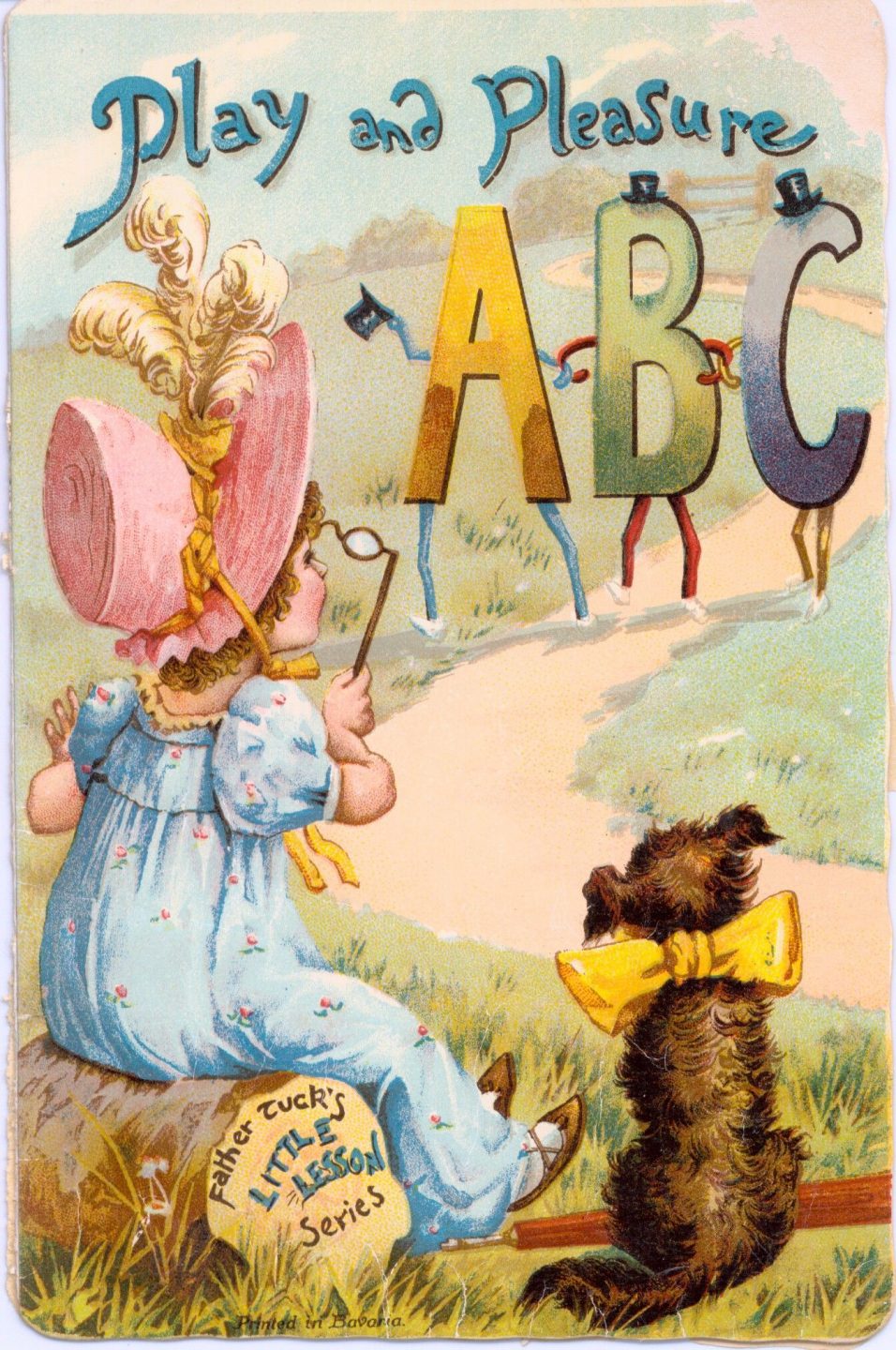

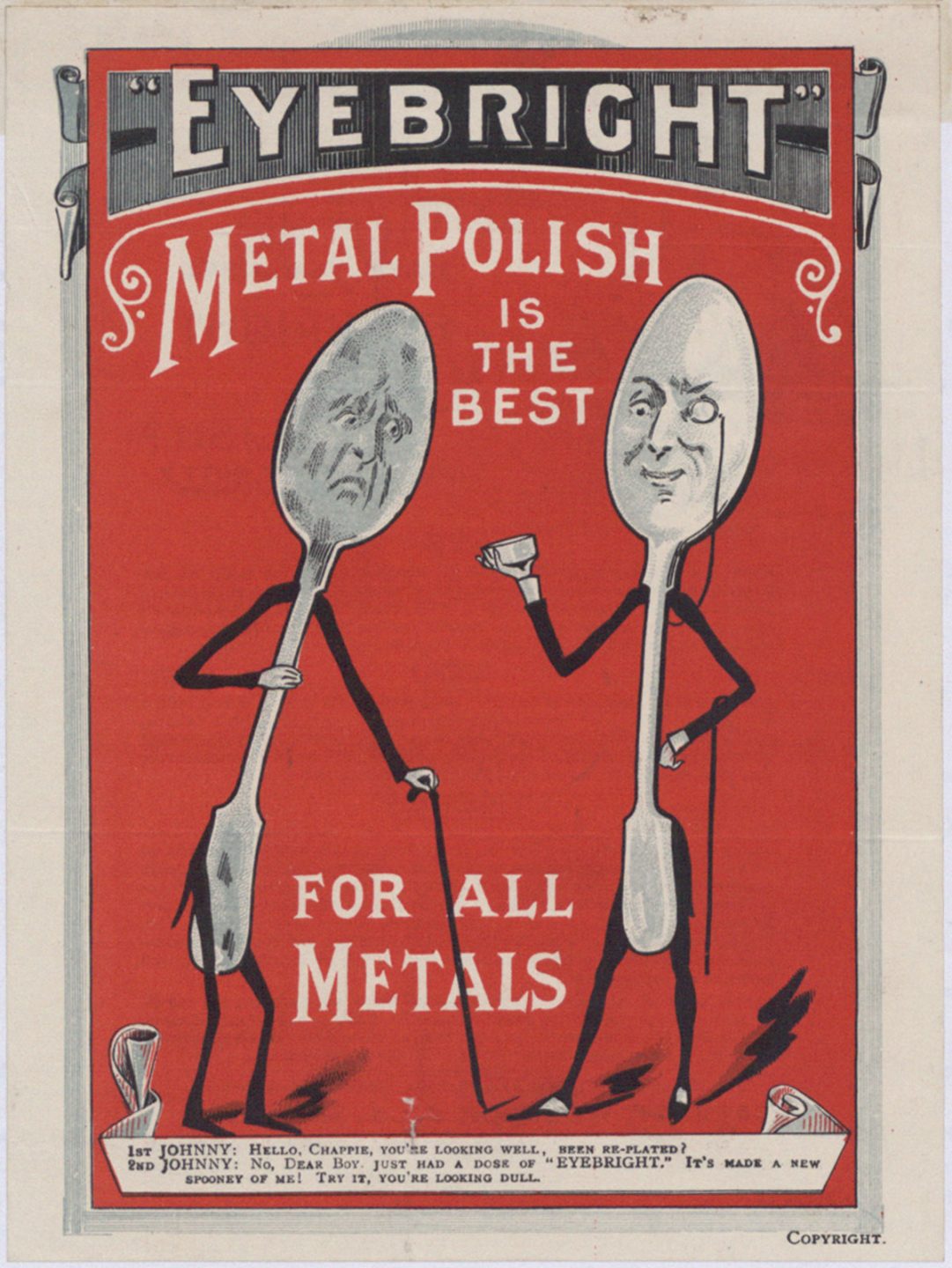

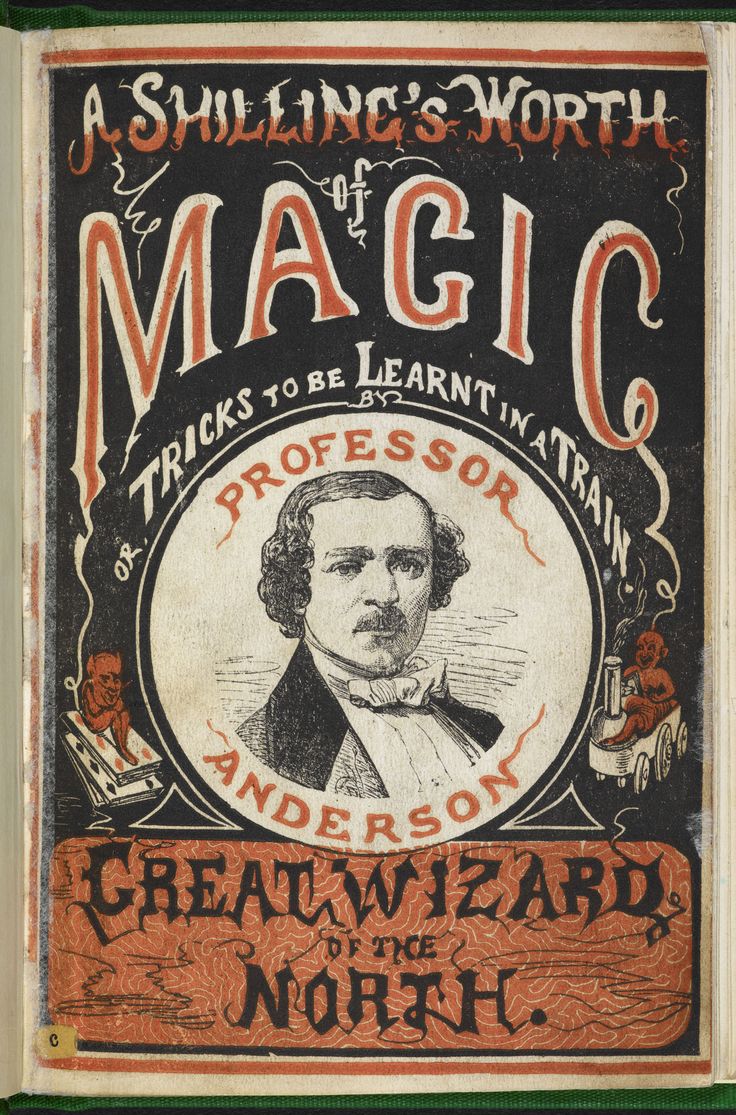

One of the hallmarks of the Victorian era, which immediately followed the industrial revolution, is the vast amounts of printed materials that were available to the public. Countless examples of posters, packaging, advertisements, and ephemera infiltrated the visual environment of Victorian society. New printed formats like small publications, magazines, and children’s books appeared.

Written language as a vehicle for public discourse and cultural awareness has a history that reaches back to ancient times. An early example is the code of Hammurabi which was created in 1754 BCE by the Babylonians—a civilization that succeeded the Sumerians in the area known as Mesopotamia. One of the oldest deciphered writings in recorded history, the code of Hammurabi is a column-like structure made of black diorite which, through inscribed cuneiform, details all of the codes and laws of the Babylonian Empire. Named after king Hammurabi who commissioned its creation, the stone stele was placed in a prominent public temple where it could be observed and accessed by the entire community.

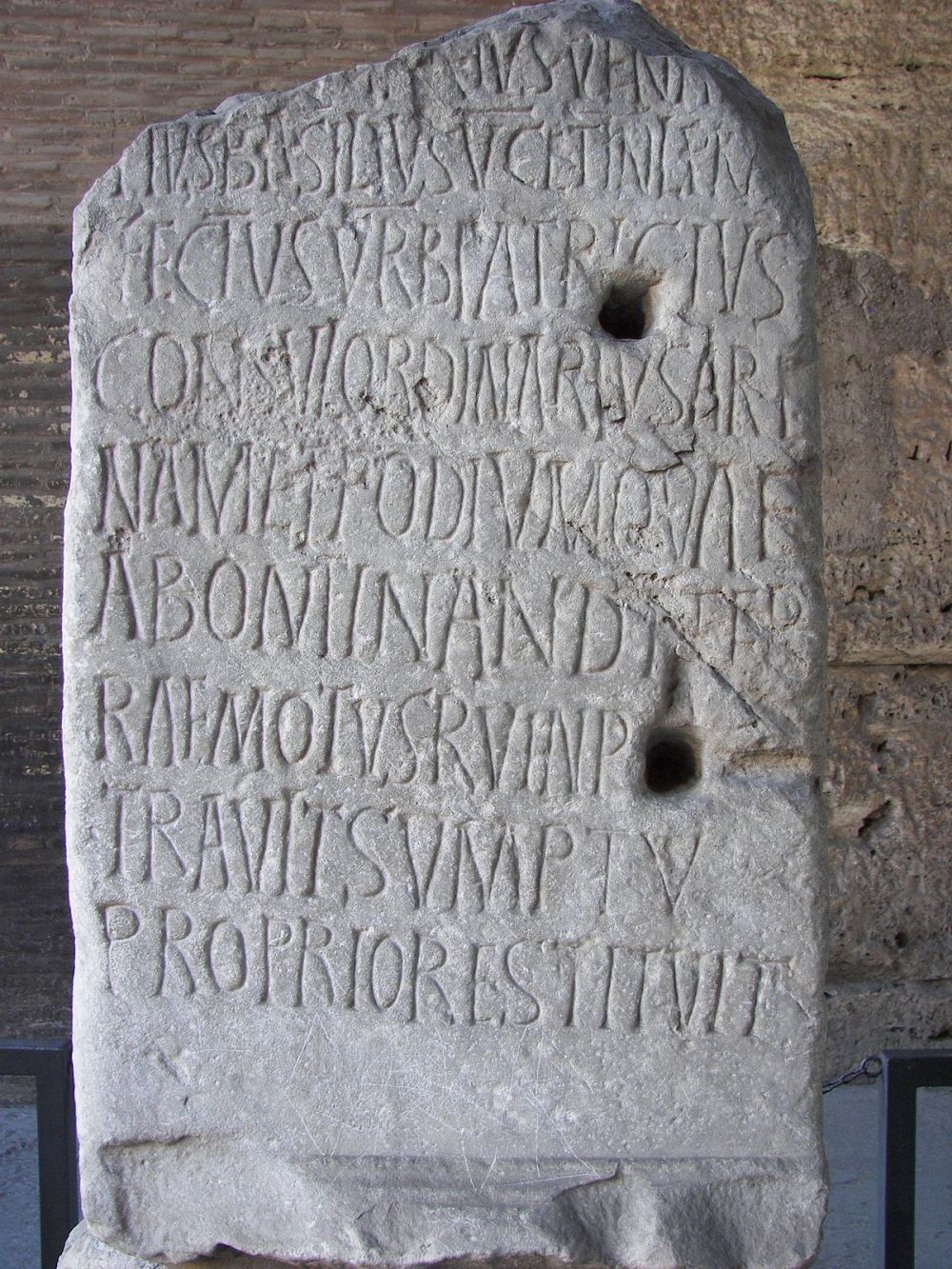

This practice of connecting the public to information on governance and policy was also practiced by the ancient Romans. The Acta Diurna—which roughly translates to daily public records or “daily acts”—was a carved stone or metal message board which was displayed in the public square and contained a collection of important public notices, events from court rulings, and decrees from the emperor. The Acta Diurna was initiated by Julius Ceasar in 59 BCE and is considered the precursor to modern-day newspapers.

Another early example of the dissemination of information are the ancient gazettes of China called Dibaos. These publications were written on materials ranging from bamboo to silk and contained official reports or bulletins from the government of imperial China. The earliest examples date back to the Han Dynasty in the third century CE.

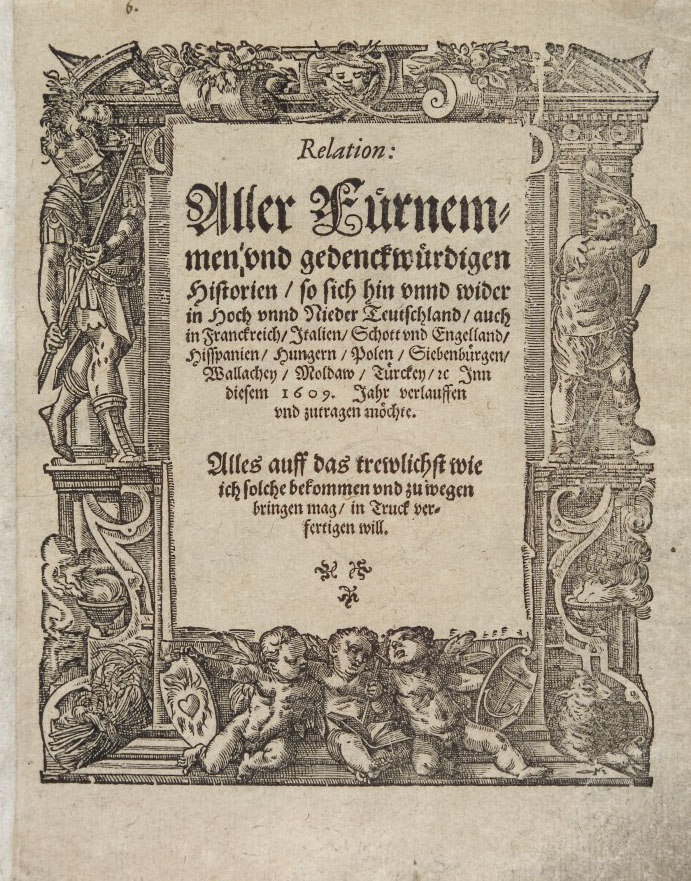

After the development of the printing press in Europe in 1450, many periodicals and newspapers devoted to reporting on politics and current events began to develop throughout Europe during the 17th century in countries such as Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands. These publications were text only at first, but later incorporated imagery through woodblock and later halftone printing. During the industrial revolution many cities in Europe, as well as North and South America, began to create newspaper-type publications.

The Victorian Perspective

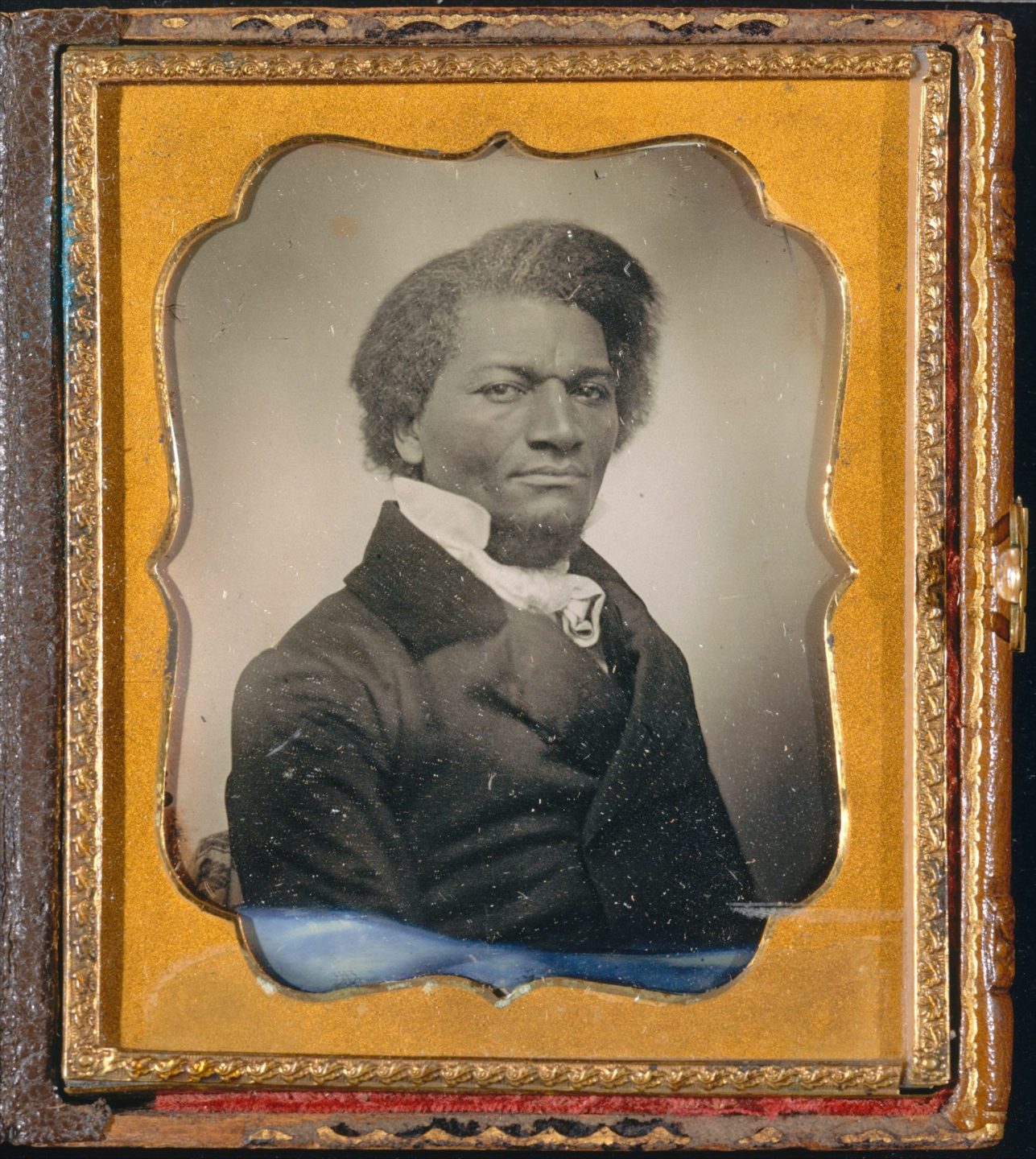

The Victorian era is marked by the duration of the reign of Queen Victoria in England from 1837 to her death in 1901. This period begins at the final stage of the industrial revolution and represents a time when the effects of new technologies begin to inform cultural perceptions of value, shape public policy, and generate social reform. This period also marks a time when, being the center of the new industrial age and, at the same time, aggressively amassing its colonial empire, England had a significant impact on the rest of the world. Beginning in the 17th century, the British empire began to rapidly expand into territories in Africa, Asia, and the Americas. The first British settlement in the Americas was founded in 1607 in Jamestown. In 1672, England set up territories along the coast of West Africa whose main function was the export of West African resources—one of which being the inhabitants of the region. By the 1800’s, Britain would transport 3.5 million Africans to the Americas.

Victorian Design

From the perspective of design and aesthetics, the Victorian era is a time when past styles were being mixed together and ornament, decoration, and opulence were highly favored. Many new technologies developed during this time contributed to the distinct characteristics of a Victorian visual approach.

The sensibilities of Victorian aesthetics can be seen as an important halfway point between the traditional perspectives of the classical, pre-industrial Europe and the impact of emerging technologies which would transform cultural definitions of beauty, value, and legitimacy.

Before the industrial revolution, value had been defined by skill and labor. The cultural regard for visual styles which incorporated intricate detail and delicate pattern derived in part from a recognition of the craftsmanship and resources that went into their execution. The cost of something aligned with the time, skill, and craft required for its production. New industrial processes completely changed the relationship of human endeavor and the perception of worth. Production methods of the time could replicate the “look” of what had previously been the result of time consuming craft and handwork. Complex and elaborate motifs used as elements within furniture and other consumer goods could now be produced quickly and cheaply.

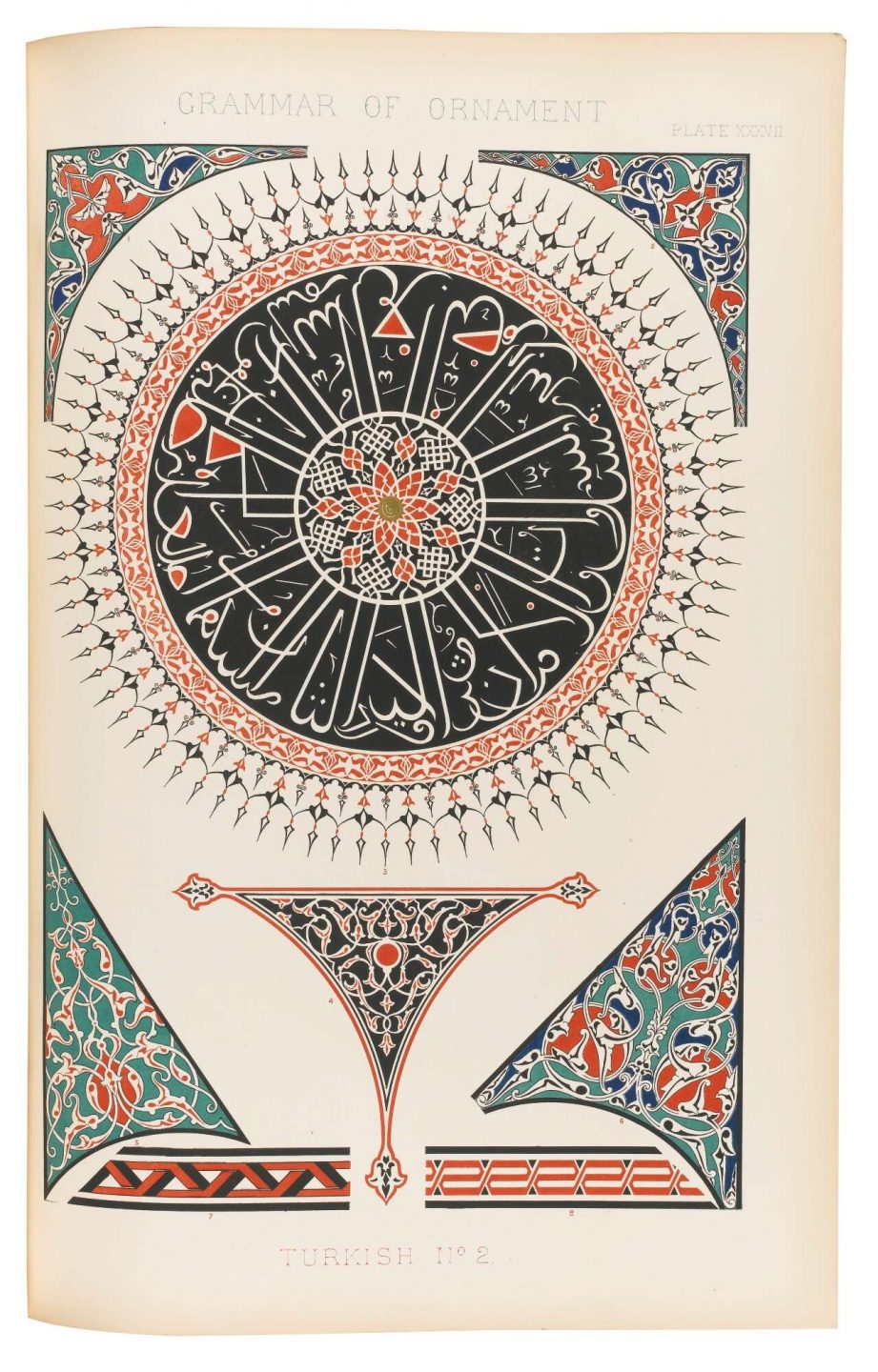

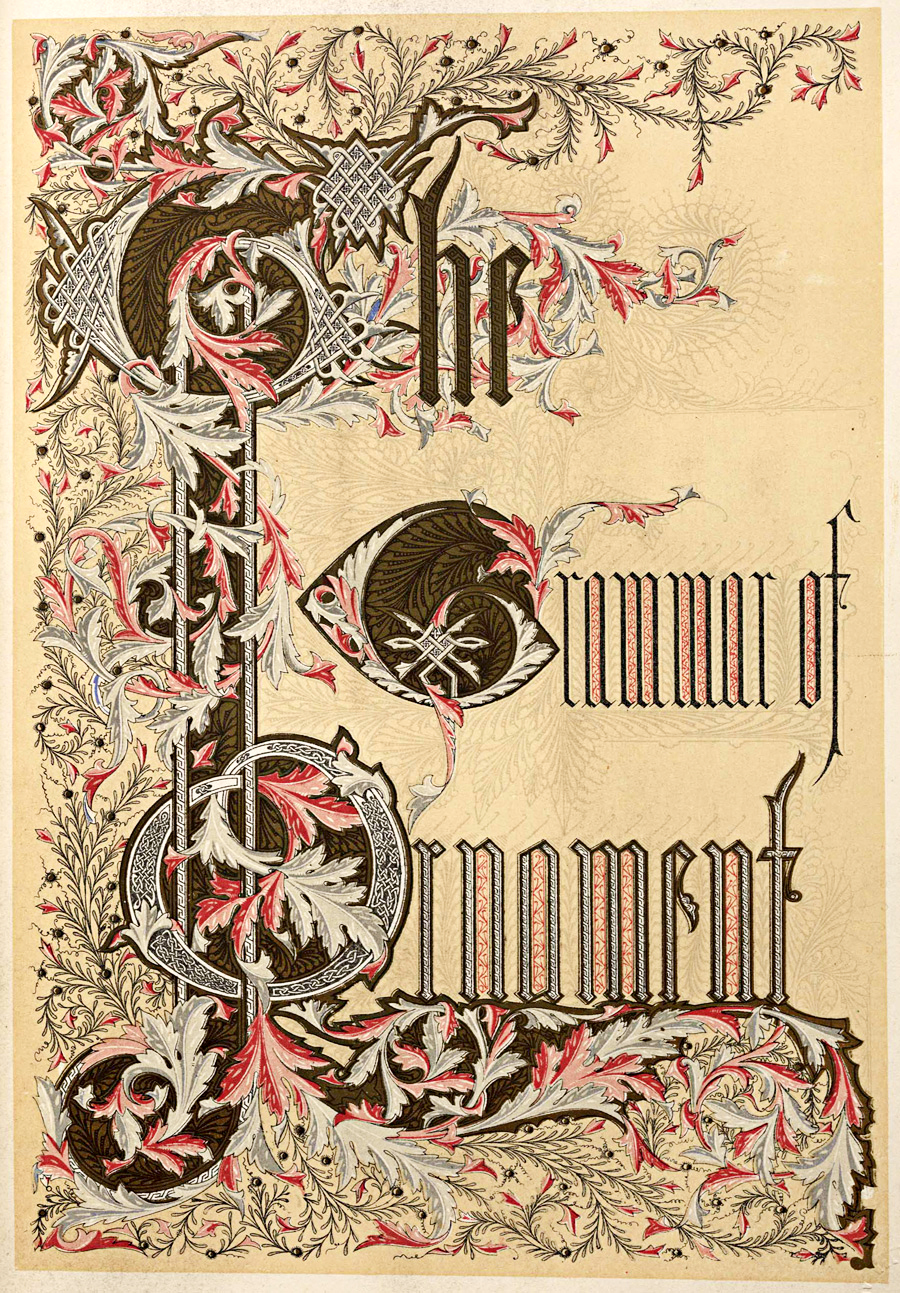

The Grammar of Ornament

Within the new formats of printed materials of the Victorian era were books and publications dedicated to showcasing the visual styles and approaches of other cultures. One such example was The Grammar of Ornament written by Owen Jones in 1842. Owen Jones was a prominent architect and the design theorist in England during the 1800’s. The Grammar of Ornament featured examples of designs Jones encountered when traveling the world in his twenties and included examples of Islamic, Spanish, and Egyptian works, among others.

Jones was also responsible for the interior design of the Great Exhibition of 1851—an event that took place in Hyde Park in London and featured an international survey of industry, technology, and design of the time. The exhibition was organized by Queen Victoria’s husband Prince Albert and was attended by over 6 million visitors. The centerpiece of the event was the Crystal Palace—a cast iron and glass structure which incorporated cutting edge developments in architecture and technology. Jones oversaw the decoration of the Crystal Palace and the arrangement of the exhibitions it housed.

The Crystal Palace and its accompanying exhibits were meant to illustrate man’s triumph over nature. Progress and conquest were the defining themes of the exhibition. On display were artworks and artifacts from newly conquered European territories. Also featured were recent inventions like early daguerreotype photography and the newly developed process of chromolithography.

Chromolithography

Lithography—or stone printing—was invented in 1796 by Bavarian author Aloys Senefelder. Lithography is a process where an image is first drawn on a large stone slab with an oil based pencil. The stone is moistened with water, then, the areas drawn with the pencil repel the water— as oil and water do not mix. When the surface is coated with an oil based ink, the ink only adheres to the area where the image is drawn—this area translates into the printed design.

In 1837, French printer Godfrey Engelmann patented the process of chromolithography—using the lithographic process to create full color images by separating them into a series of different colored printing plates. Later in 1846, American inventor Richard M. Hoe perfected the rotary lithographic press that could print six times as fast as the original flat bed lithographic press.

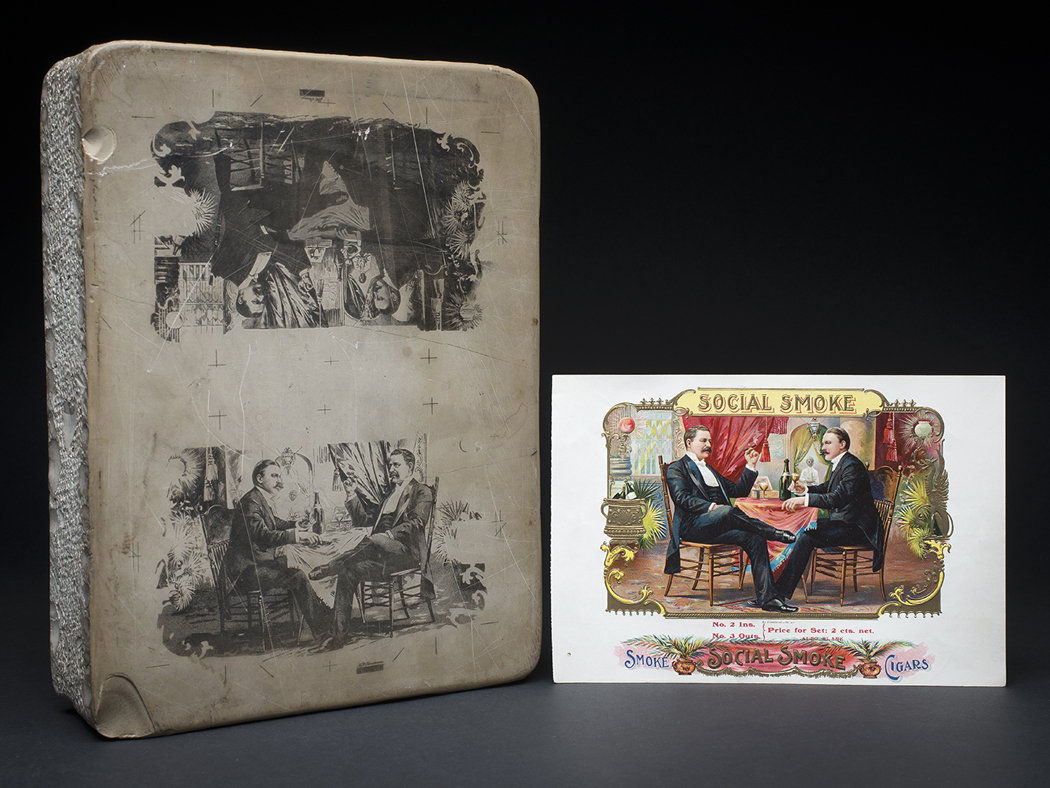

Lithography and chromolithography freed designers and illustrators from the linear confines inherent in the format of the type-bed used in the standard movable type printing process. It presented the opportunity to create letter-forms that curved, slanted and bended in countless directions. It also presented limitless freedom of form. The designer was no longer bound to the process of carving letter-forms from wood or metal; the characters could now be drawn by hand. Chromolithography is also one of the first practical methods of combing multiple colors together to achieve the full color image.

The process of Chromolithography defined the visual aesthetic of graphic works from the Victorian era. Colorful packaging lined the shelves of shops, chromolithographic prints were commonly found in people’s homes, and the colorful illustrated style associated with the process was a perfect fit for the format of children’s books which became popular during the Victorian period.

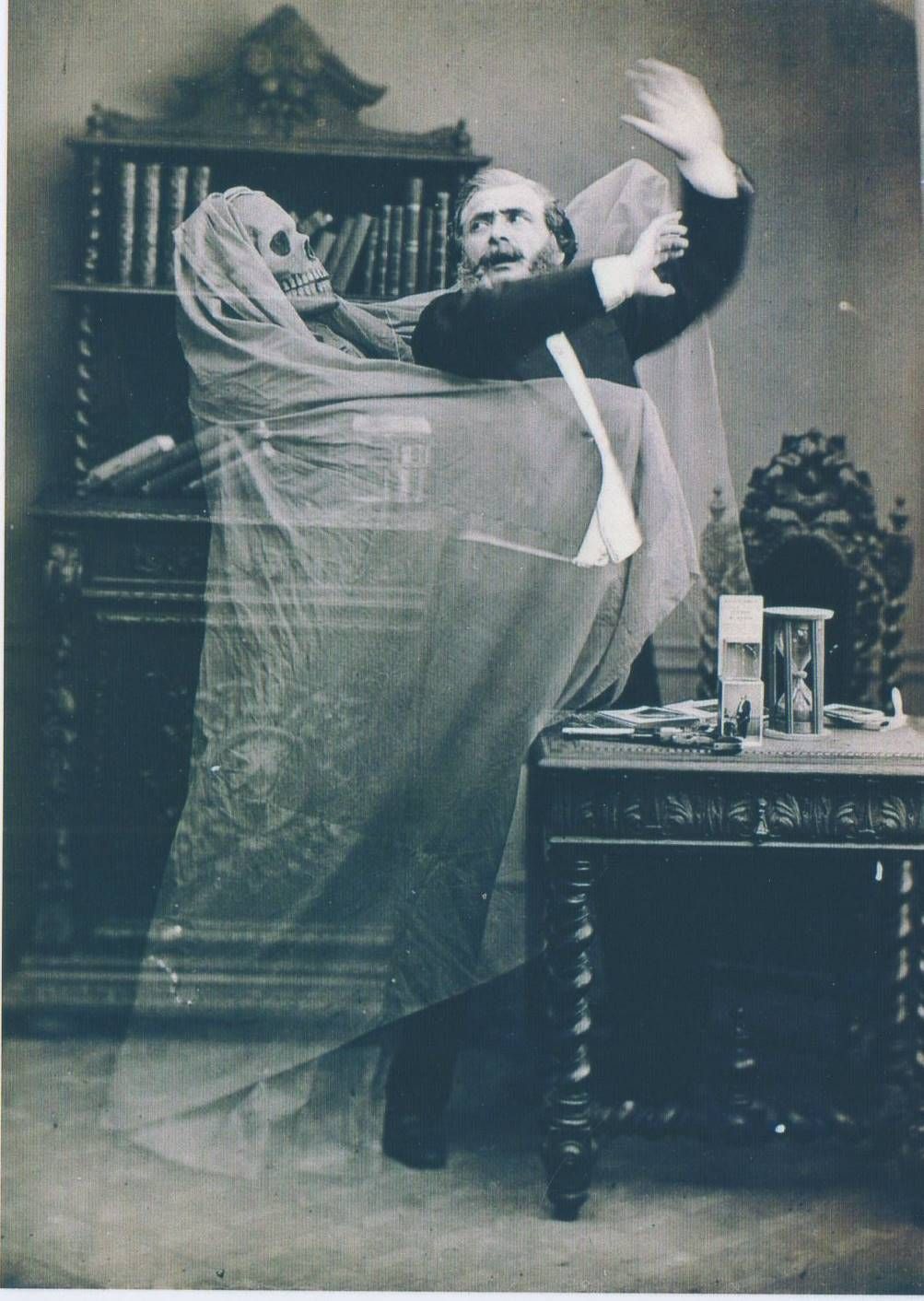

Photography

The birth of photography began in France in 1826 with experiments by Joseph Niepce and Jacques Daugerre. These initial developments led to the invention of the daguerreotype—a process in which a silver-coated copper plate is made light sensitive—then exposed in a light-proof box. This beginning led to many other development by pioneers like Henry Fox Talbot and George Eastman who is responsible for the release of the Kodak camera in 1888 which brought the innovation of photography to the masses. In the context of printing, the process of photoengraving was developed by John Calvin Moss in 1871 and was used to create an etched plate that was incorporated into the letterpress printing process. At first this process only worked for high contrast linear designs or artwork. At first, there was no method of successfully incorporating the new technology of photography into the printing process. Photography required subtle gradients to achieve clarity. Woodblock prints and chromolithography both utilized high contrast imagery. In the late 1800’s Stephen Horgan and Frederick E. Ives separately contributed to the development of the halftone screen which uses dots to create continuous tonal areas enabling the reproduction of photography within the printing process.

The development of photography presented a new visual format that generated new opportunities for visual documentation and creative expression. The presence of this new method of image-making also led to a shift in the function of art within society. Up until the advent of photography, one of the key roles of art-making had been visual representation—it was a means of recording and interpreting human experience. With the introduction of photography, the need for realistic representation diminished which freed artist, illustrators, and sculptors to depart from literal depiction. This set the stage for the stylization, expression, and abstraction which would define the ensuing avant garde movement.

The Victorian Backlash

Though the Victorian era is a time when goods and services were being produced on a scale like never before, the resulting products were of poor quality. They lacked the artistry, attention to detail, and regard for materials that characterized the works of pre-industrial Europe. There were no standards guiding production; there was no cohesive sense of design. In the quest to find cheaper and faster ways to make more products, quality and craftsmanship were lost.

There emerged a movement who rejected the maximalism of Victorian culture. This community recognized that in the mass production that defined Victorian era consumerism, there was a loss, not just of quality, but of meaning, experience, and connection. This movement longed for the design approaches and production methods of the past. They sought to return to pre-industrial standards of quality. They used past examples as inspiration for the present and future.

What began as a rejection of Victorian values and production methods eventually resulted in the utilization of these new technologies in service of craftsmanship and design. The Arts and Crafts Movement represents the merging of design and technology and would serve as a foundation for future designers throughout Europe and beyond.

Charles Whittingham was a British printer and book designer who set up a studio in London called the Chiswick Press, where he created books which incorporated Renaissance and pre-Renaissance styles and production methods. He looked back to type designers like Nicolas Jensen, William Caslon, Claude Garamond, and the Aldine Press for inspiration. His practice arose out of a love for high quality books. He painstakingly labored over every detail and combined elements of handwork with advanced production methods available at the time. In the mid 1800’s he began to collaborate with the publisher William Pickering to produce some of the most well designed books of the era.

By age 24, Pickering owned a bookshop which specialized in rare books that were made before the arrival of the new industrial processes of the Victorian era. He was one of the first individuals to apply the new methods of production in service of design thinking. In the structure of his studio, we see for the first time in history a person specifically dedicated to design concerns—someone who would oversee the production, layout, typesetting, and all other visual considerations. He was the first to conceive of the role of designer as a necessary part of book production. His work featured the revival of Gothic design elements as well as books that centered on education and information design.

Another London printer working with similar aims was Emery Walker. He was part of a private press called the Doves Press which formed in the late 1800’s and was dedicated to creating works which utilized elevated design and typography.

William Morris and the Century Guild

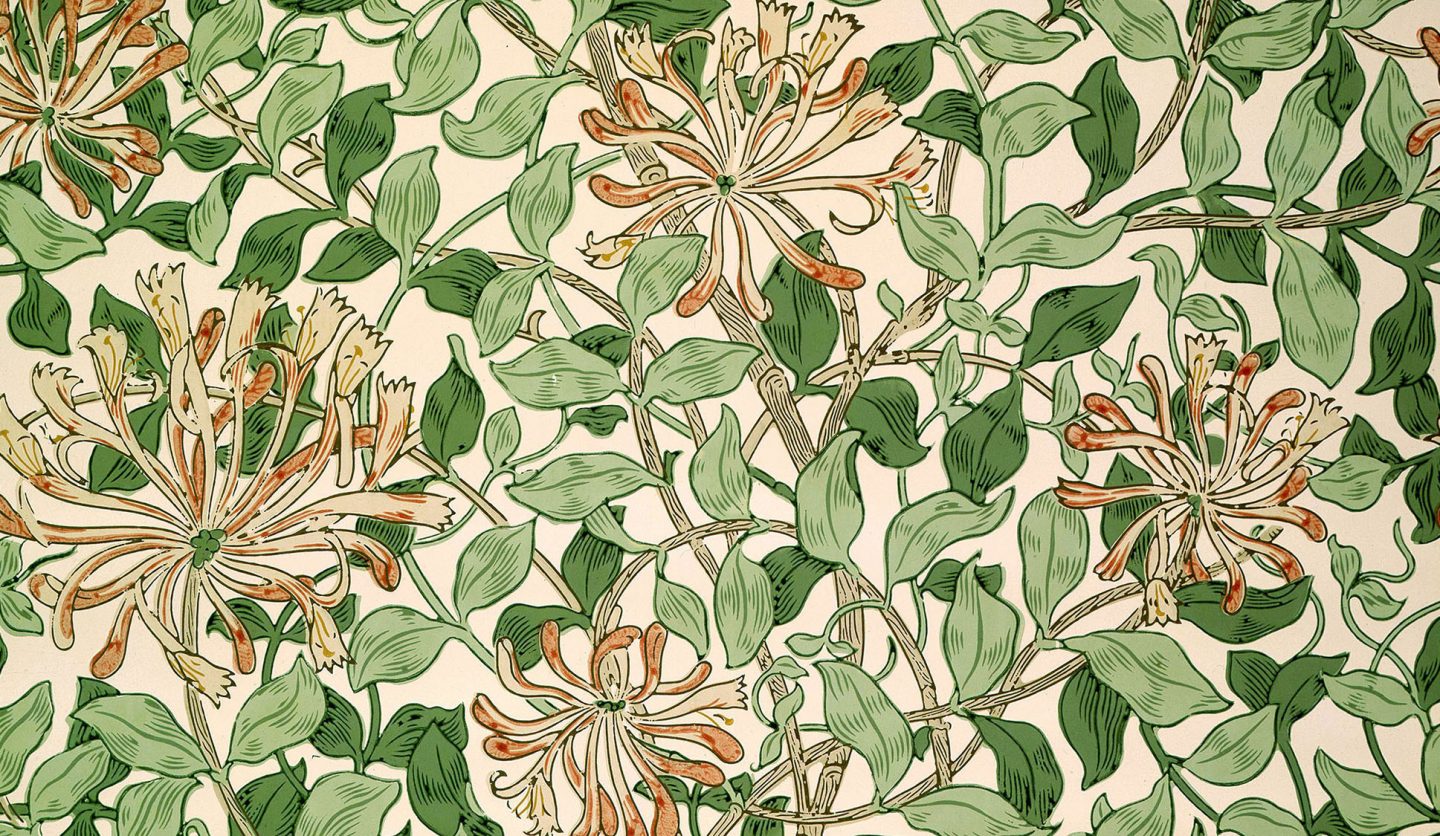

William Morris was a prolific designer who created furniture, stained glass, wall paper, tapestries, and eventually books and typefaces. His dedication to craft, quality of materials, and quality of design resulted in work that would become internationally recognized in his lifetime. He began his career as part of a student group at Oxford university in the 1850’s who sought to, through their creative work, advocate for social reform. They believed that art and design played a significant role in society. They regarded the individual fields of art, design, and craft with equal measure and believed the practices to be interconnected. This approach served as the basis for the name and ethos of the Arts and Crafts movement.

In 1861, Morris began his career producing furniture and designing interiors. He oversaw both the aesthetic conception and manufacturing of the furniture, stained glass, tapestries, and housewares he incorporated in his work. His vision of an integrated creative practice would serve as a vital inspiration for future movements to come like Art Nouveau and the Bauhaus.

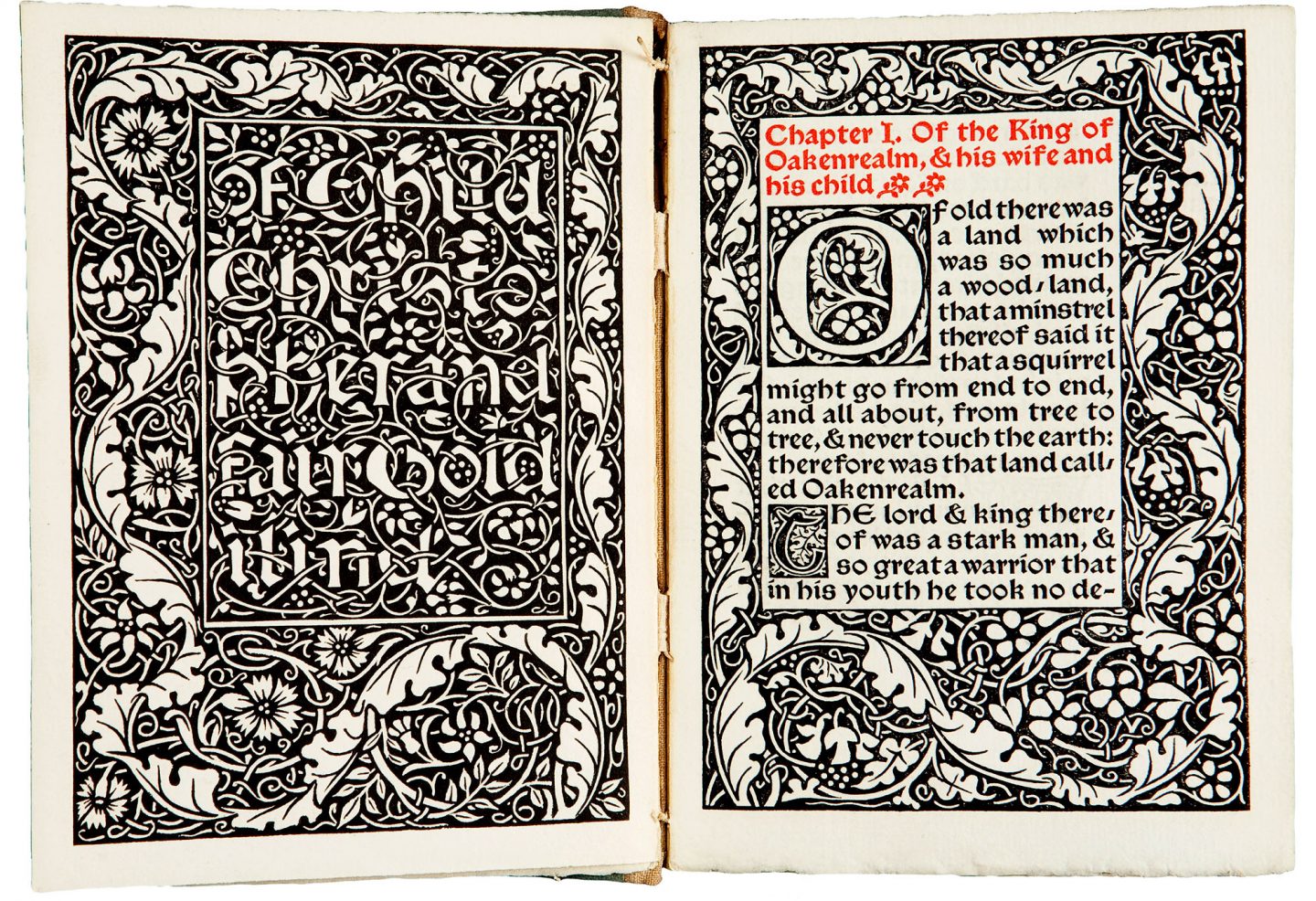

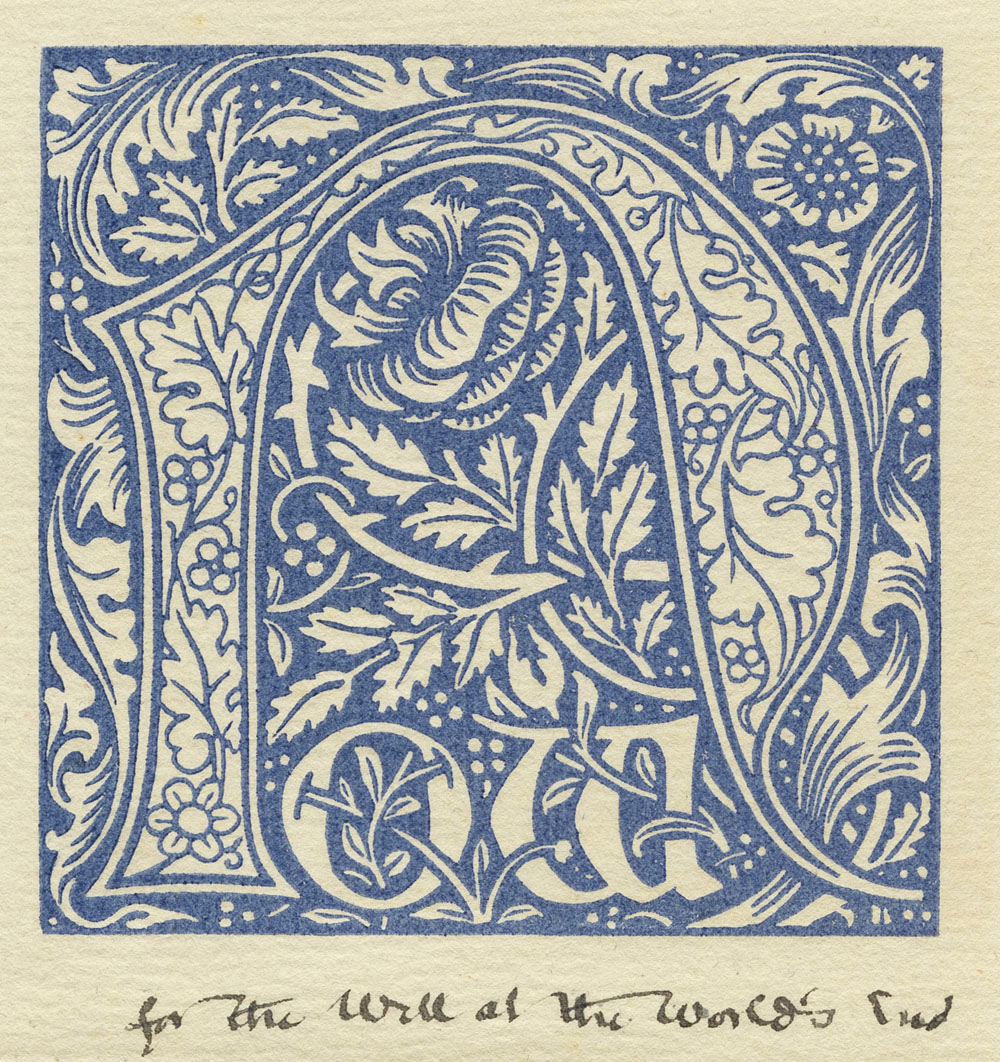

In 1888, Morris began to experiment with book and type design. He designed a typeface called Golden after the designs of Nicolas Jensen first created in Venice in the 1470’s. He designed books that referenced Medieval and Renaissance designs. His first books he published with the Chiswick Press and Doves press; finally opening up his own press—the Kelmscott press in 1890. Kelmscott publications featured ornate woodblock illustrations from prominent artists along with Morris’s hand cut typefaces.

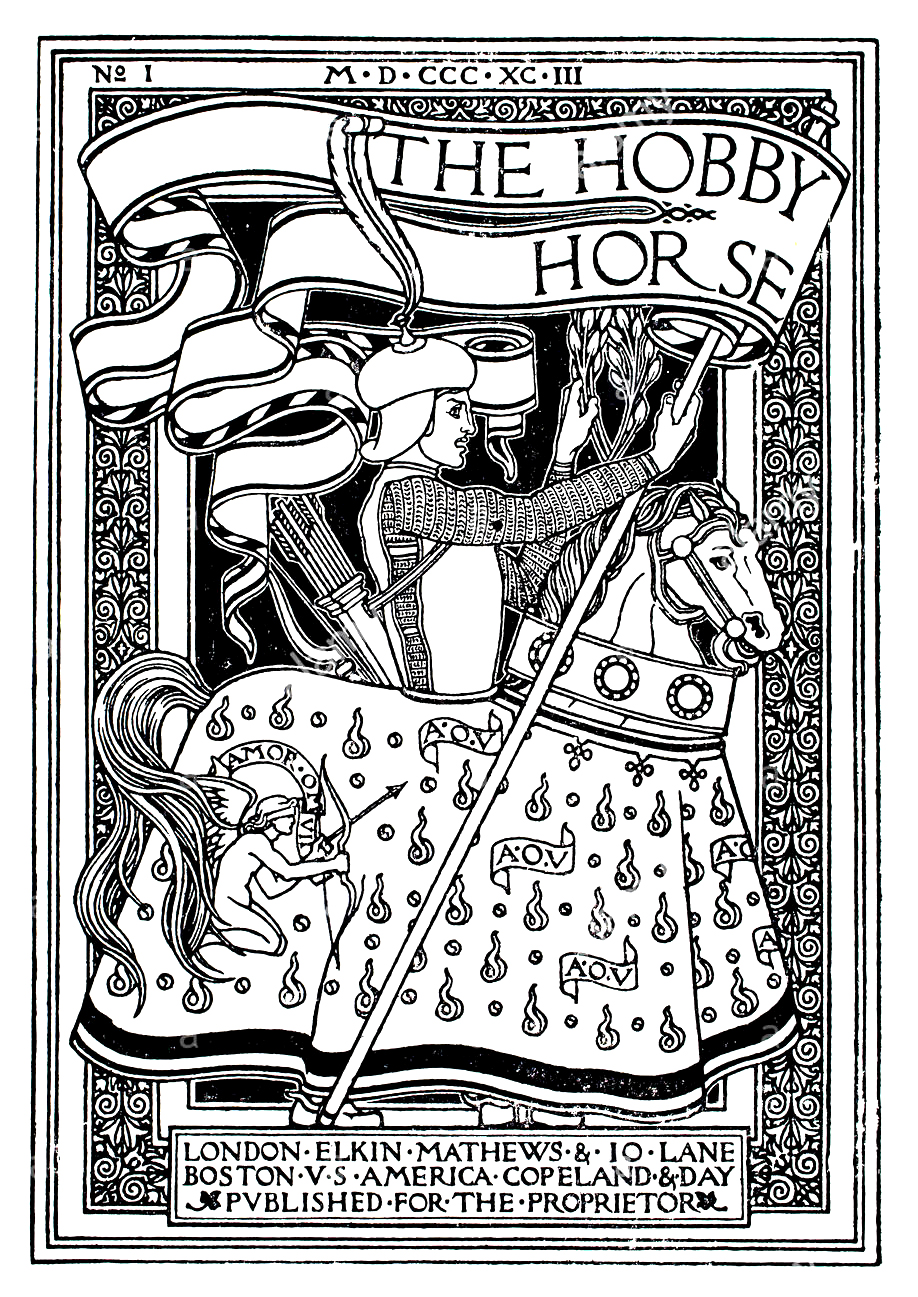

Another group that emerged during this time was the Century Guild—a group of artists and art enthusiasts who worked in and around London between 1883 and 1892. The group was founded by English architect Arthur Mackmurdo and English designer Selwyn Image. They began a quarterly magazine in 1884 called The Hobby Horse. The magazine would be an important vehicle for spreading the philosophy of the Arts and Craft movement to other parts of Europe and beyond. The Guild primarily produced domestic design such as furniture, stained glass, metalwork, decorative painting and architectural design. The aesthetic approach present in their work marks the early beginnings of the Art Nouveau style.

The Arts and crafts movement represents an important cultural example of a community who, through creative response, pushed against prevailing systems. In the midst of the hyper industrialization and resulting incessant consumerism of the Victorian era, this movement questioned and ultimately amended the prevailing approaches to design and manufacturing. They rejected new and emerging industrial fabrication methods centered on mass production in favor of traditional techniques. These new industrial technologies were eventually utilized in service of craftsmanship, quality, and aesthetic vision. The ethos of the Arts and Craft movement—applying new technologies for the sake of elevated design—would become an inspiration for many designers and design movements in the years to come.

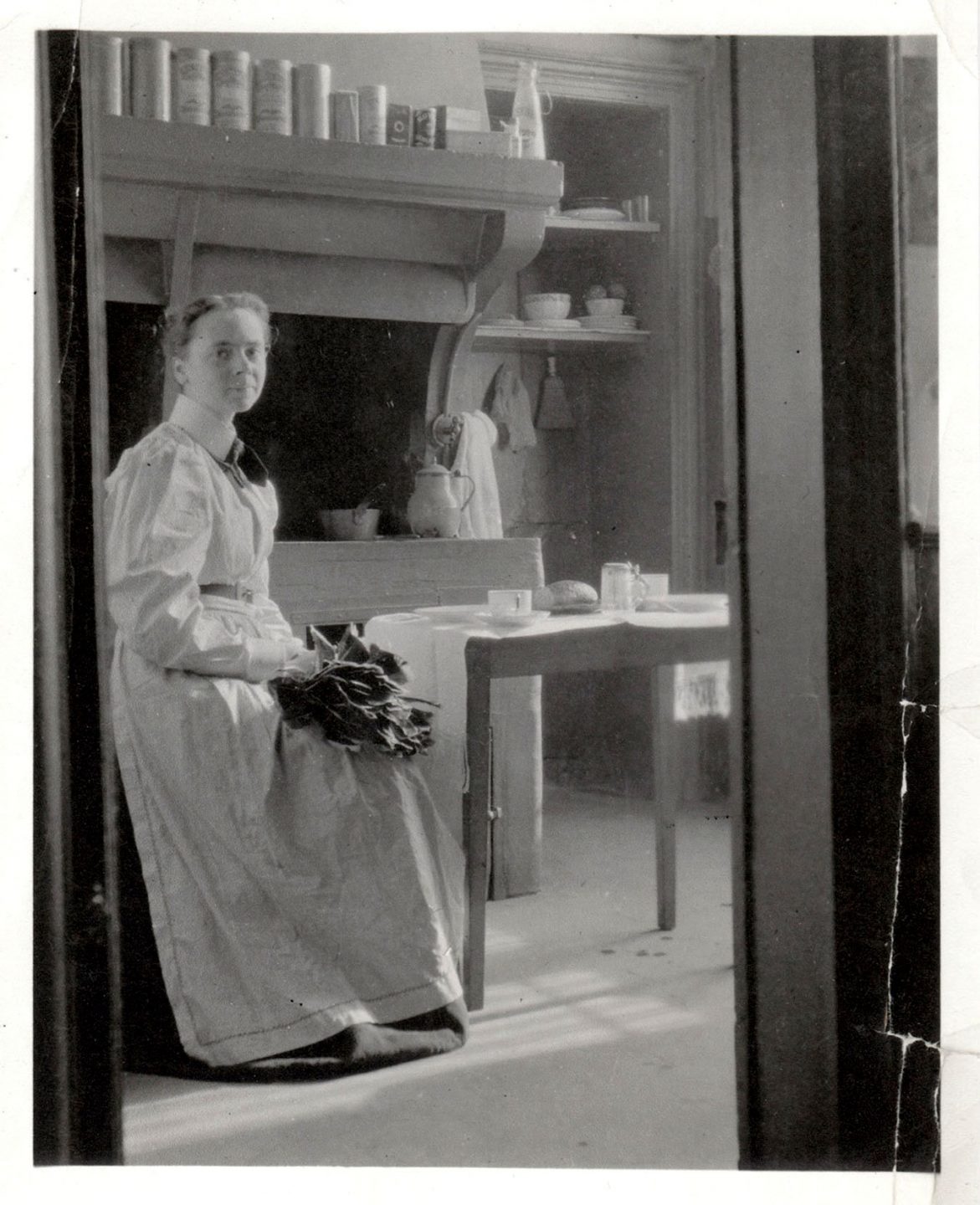

The merging of art, design, craft, and technology was a vital component of the Arts and Crafts philosophy. This integration of creative fields had the effect of elevating vocations which centered on handwork and technical skill and acknowledged them in the same context as traditional fine arts practices which had historically been categorized as intellectually superior. The strict hierarchy inherent within the realm of fine arts in Europe had been an impediment to women entering creative pursuits throughout the middle ages and the Renaissance. The Arts and Crafts Movement’s merging of creative practices opened the door for women to pursue art and design as a career. Many of the disciplines within the movement centered on the domestic sphere—furniture, ceramics, jewelry, ornament, decorative arts—providing further opportunity for female artists and artisans.

One of the prominent female figures of the Arts and Crafts Movement was William, Morris’s daughter May Morris. Though often overshadowed by the work of her father, she is considered one of the most renowned designers of embroidery and jewelry within the Arts and Crafts community in Britain. In reaction to many of the art guilds and organizations excluded women from becoming members and exhibiting their work, May Morris founded the Women’s Guild of Arts in 1907. This organization provided a crucial platform for showcasing and promoting the work of female artist and designers of the time.

In America, the Arts and Crafts movement arrived at a time when the early suffragette movement was beginning to form in the fight for the right of women to vote. Many women were seeking independence and the opportunity to develop careers of their own. The Arts and Crafts movement in the US produced many notable female designers including the jewelry designers Florence Koehler and Marie Zimmermann.

Another prominent figure is the architect Julia Morgan. She was the first woman to be admitted to the program at l’École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris and the first woman architect licensed in California. Throughout her illustrious career, she designed more than 700 buildings including the St. John’s Presbyterian Church in Berkeley, Asilomar YWCA in Pacific Grove, and The Hearst Castle in San Simeon. Morgan is considered one the greatest American architects of all time. In 2014, she became the first woman to receive the gold medal from the American Institute of Architects.