10/27/2021

Postmodernism and Digital Culture

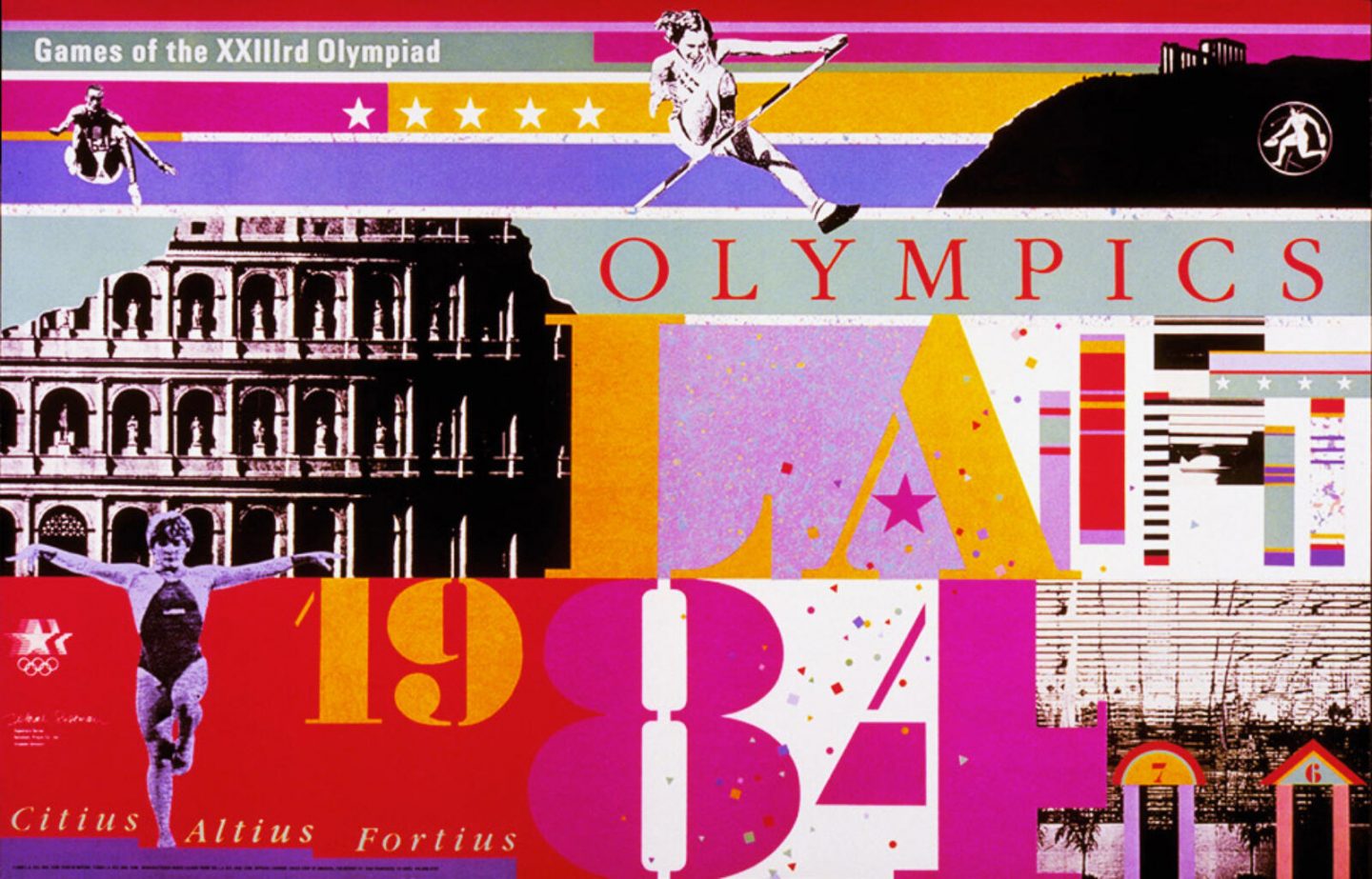

New technologies expand the field of visual communication

More is more.Deborah Sussman

In the wake of World War II, new technologies began to surface that would open up the practice of graphic design to a whole new range of audiences who previously did not have access to the means of design production. Beginning in the sixties, these demographics would begin to infiltrate the sphere of commercial design—a space that had formerly been confined to the formal settings of for-profit design studios, in-house corporate environments, and academic institutions. This new crop of creatives would bring with them a wide range of styles, approaches, and motivations that had never before been present within the field of visual communication.

This expansion of graphic expression comes at a time when the dominant style of modernism, once seen as innovative and new, starts to fall out of fashion. Modernist design’s strict criteria of san serif type, grid-based composition, and restrained minimalism, in the midst of shifting cultural perspectives, begins to read as restrictive and irrelevant—particularly to younger generations. Emerging artists and designers of the sixties and seventies were being drawn to alternate approaches. They were departing from modernist sensibilities and instead embracing the rebelliousness and experimentation associated with the counter-cultures that were forming alongside a growing number of grassroots social movements focused on achieving cultural change through protest and activism.

Because these new practitioners came from a variety of backgrounds and practiced their craft within a wide spectrum of contexts, their styles and perspectives were varied and multifarious. Some practitioners mixed elements of modernism with new styles and approaches that existed outside of the modernist oeuvre. Other designers abandoned modernism altogether. This phenomenon of multiple perspectives existing together is a defining feature of the postmodern era.

Phototypesetting

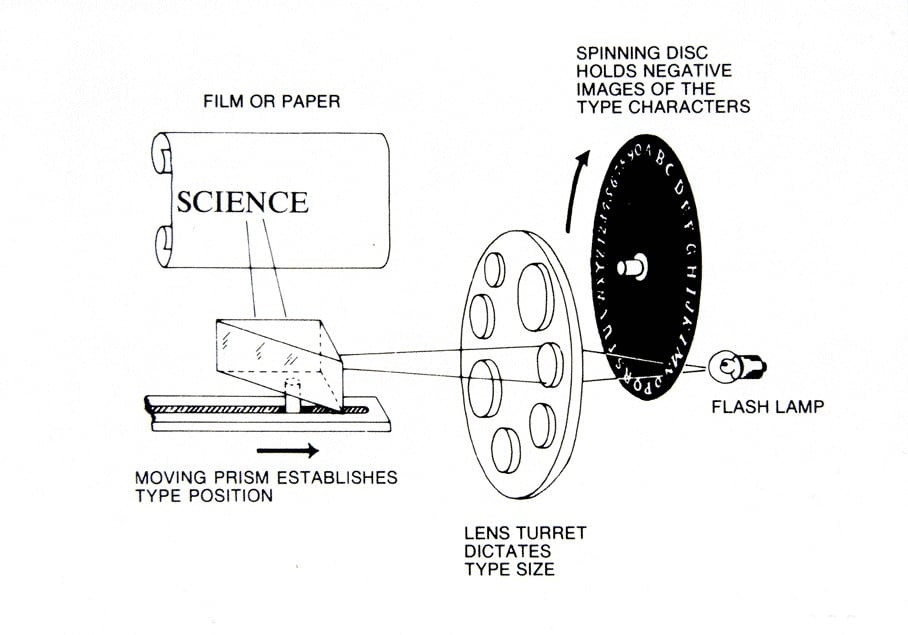

Aside from the linotype machine, the dominant production processes within the printing industry had not changed much after the war. Even Gutenberg’s signature formula for casting type—a mixture of lead and antimony—was still being used well into the twentieth century. The technology that would finally make hot metal type obsolete and act as the bridge to the eventual digital revolution of the eighties was the technology of phototypesetting.

First developed by two French engineers—René Higonnet and Louis Moyroud—the phototypesetting process involves projecting text onto a light-sensitive medium like film or treated paper which is then processed and transferred to lithographic plates for use in offset printing. Phototypesetting would completely change the printing industry. By the 1970’s almost all newspapers had abandoned hot metal type for the phototypesetting process.

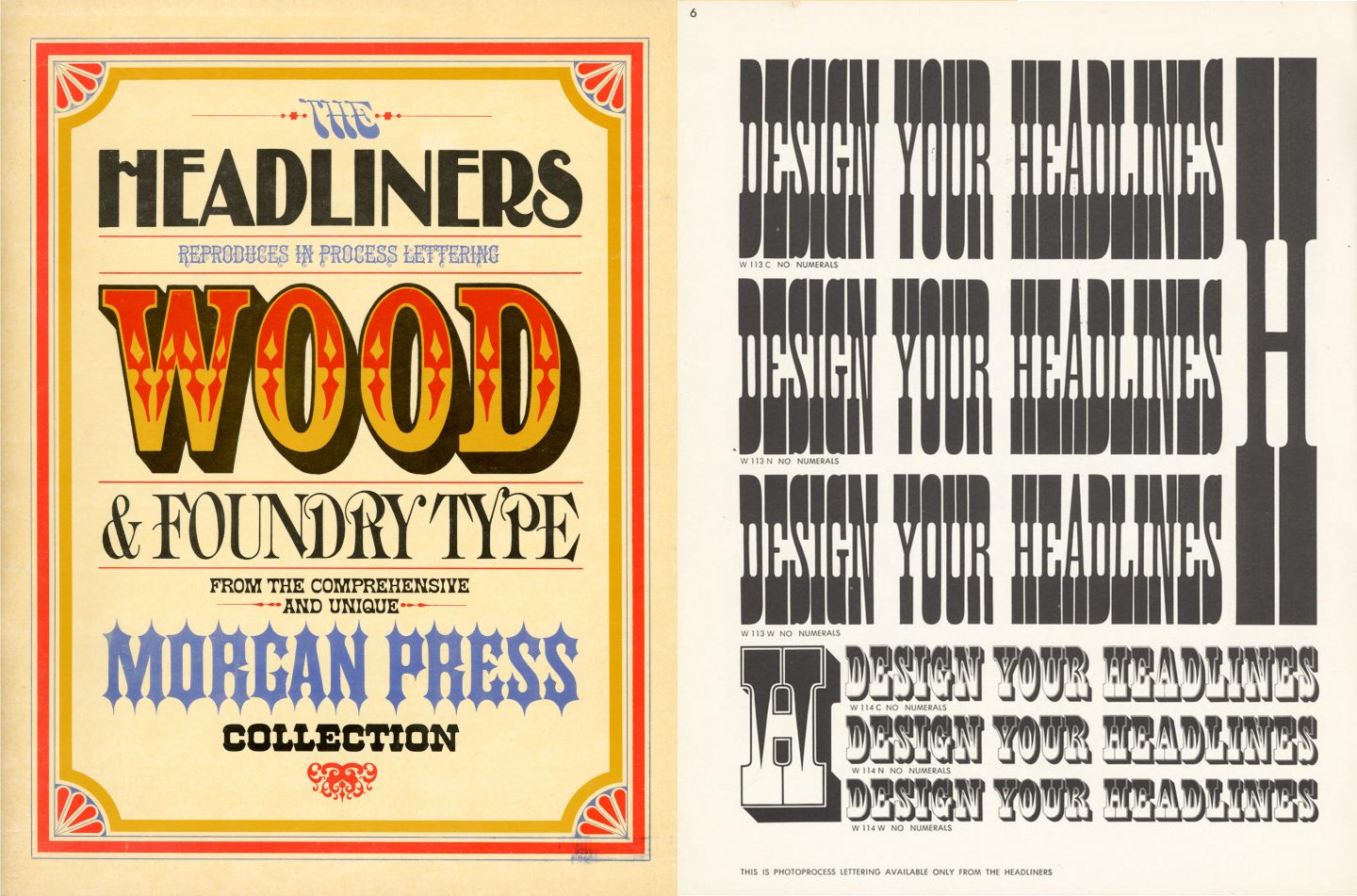

This new technology also sparked a revolution in typography. Within the cast metal process, developing new typefaces was laborious and time consuming. Each character of a new typeface had to be individually fabricated into a three dimensional matrix then cast in metal. With phototypesetting, new fonts could be created and implemented without casting, making the creation of typefaces cheaper and easier than ever before.

Phototypesetting presented the possibility of significantly expanding the pool of available typefaces at a time when the industry of design was expanding—being used in more ways by more people within new contexts. This growing field of creatives wanted more than just the typical stable of neutral san serif faces that were dominant in the modernist works of the fifties and sixties.

The development of phototypesetting coincided with an emerging interest in design history—more and more creatives were looking to the past for inspiration, particularly in the area of typography. Many designers began to depart from the future focused ethos of the international typographic style and Swiss approaches. Instead, they moved to past periods and genres for inspiration—early modernist movements, the Industrial Revolution.

Even before phototypesetting became the industry standard, many printers were beginning to collect movable type from past eras to meet a growing interest in historic styles among contemporary audiences. Once phototype replaced cast metal type, companies emerged like Headliners who converted typefaces from earlier periods—wood type, victorian— into the phototype format.

DIY Design

The xerox company released its first black and white photo-copier in 1949. By the mid-fifties the machine would become a standard fixture in modern offices. Before this invention, the copying of documents was a tedious task done by hand. As photocopiers grew in popularity, they became more and more accessible to the general public. By the seventies, photocopiers were present in many retail businesses, allowing anyone to make cheap black and white copies.

Letraset dry-transfer letters were first marketed to the public in the early sixties. The product was formatted as a series of plastic sheets containing multiple copies of letterforms within a complete alphabet that could be transferred to a dry surface by applying pressure with a small blunt instrument. Each group of sheets featured a specific typeface at a specific weight and size. You could purchase a complete set of Futura regular at 12 points, Helvetica light at 24 points, or perhaps Bodoni extra bold at 60 points. The sheets would also include punctuation and a complete set of numbers. Up until the release of letraset, typesetting was a process exclusive to design studios and print houses. Letraset put type in the hands of the general public and made the creation of typographic work cheaper and easier than it had ever been before.

Innovations like the xerox machine, dry transfer letters, and phototypesetting—in addition to the format of screen printing which first grew in popularity in the UK in the sixties and would eventually make its way to the states—don’t perhaps seem cutting edge in our age of AI and digital platforms. What made these developments so transformative is that they expanded the ability to create graphic content to a limitless spectrum of practitioners.

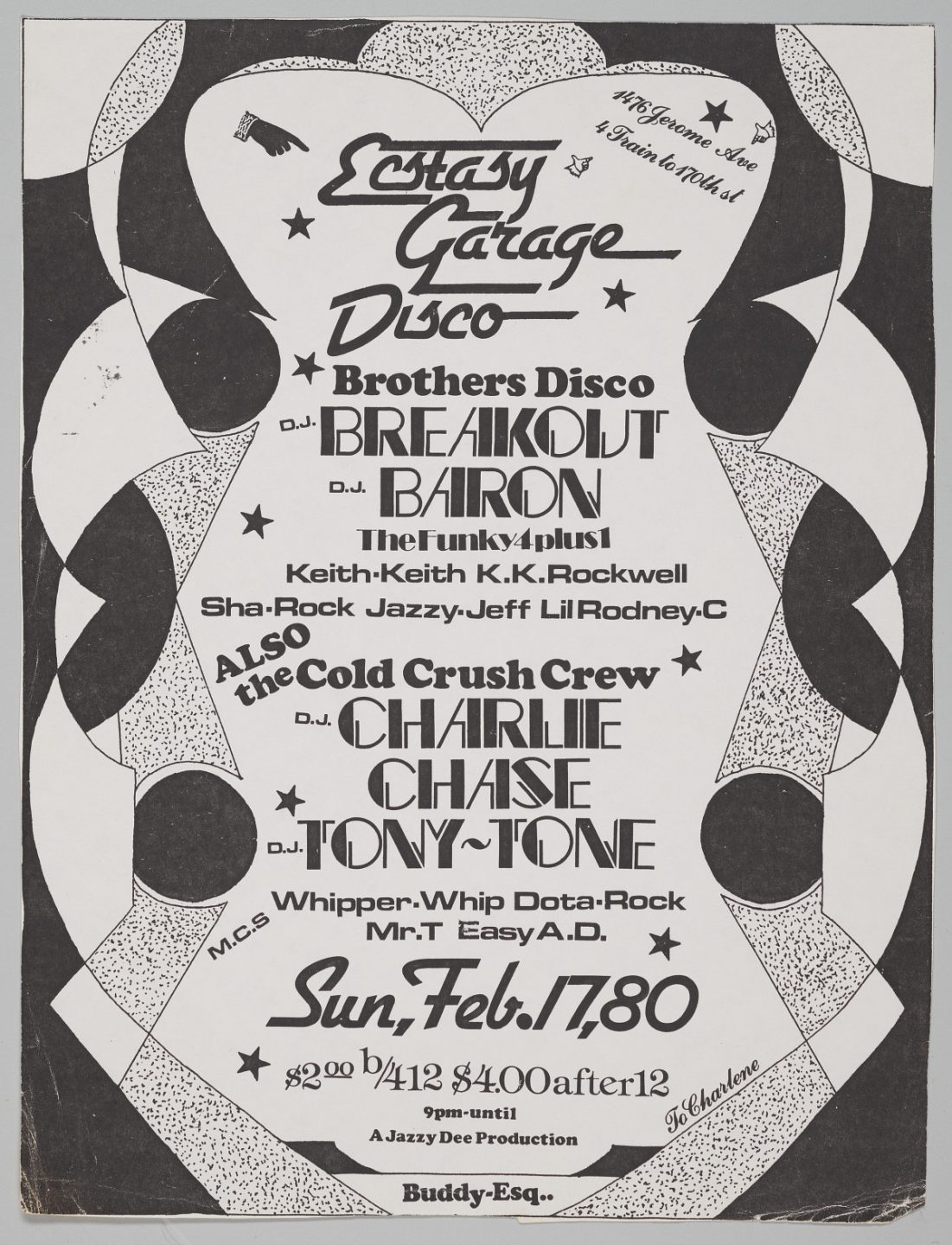

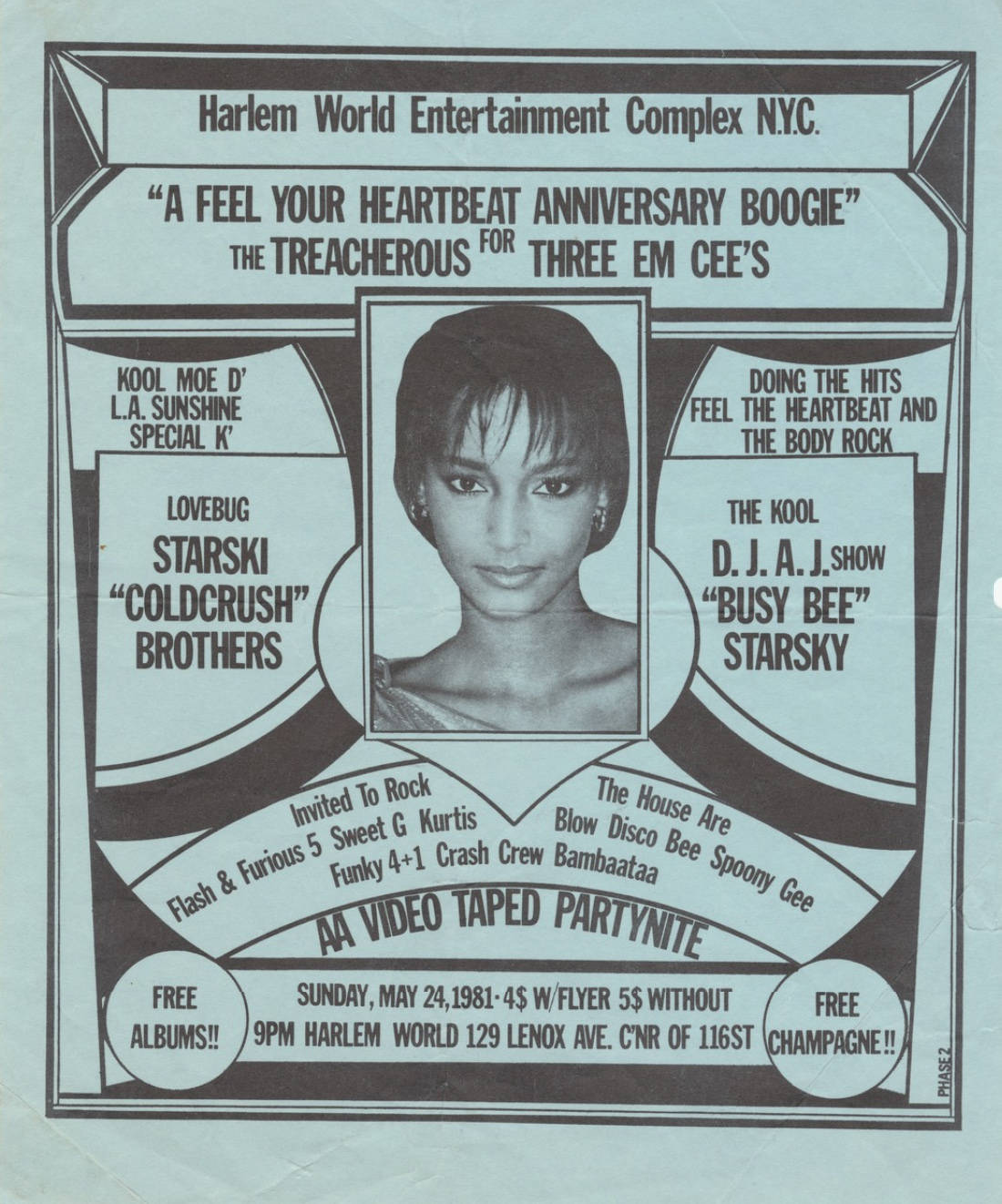

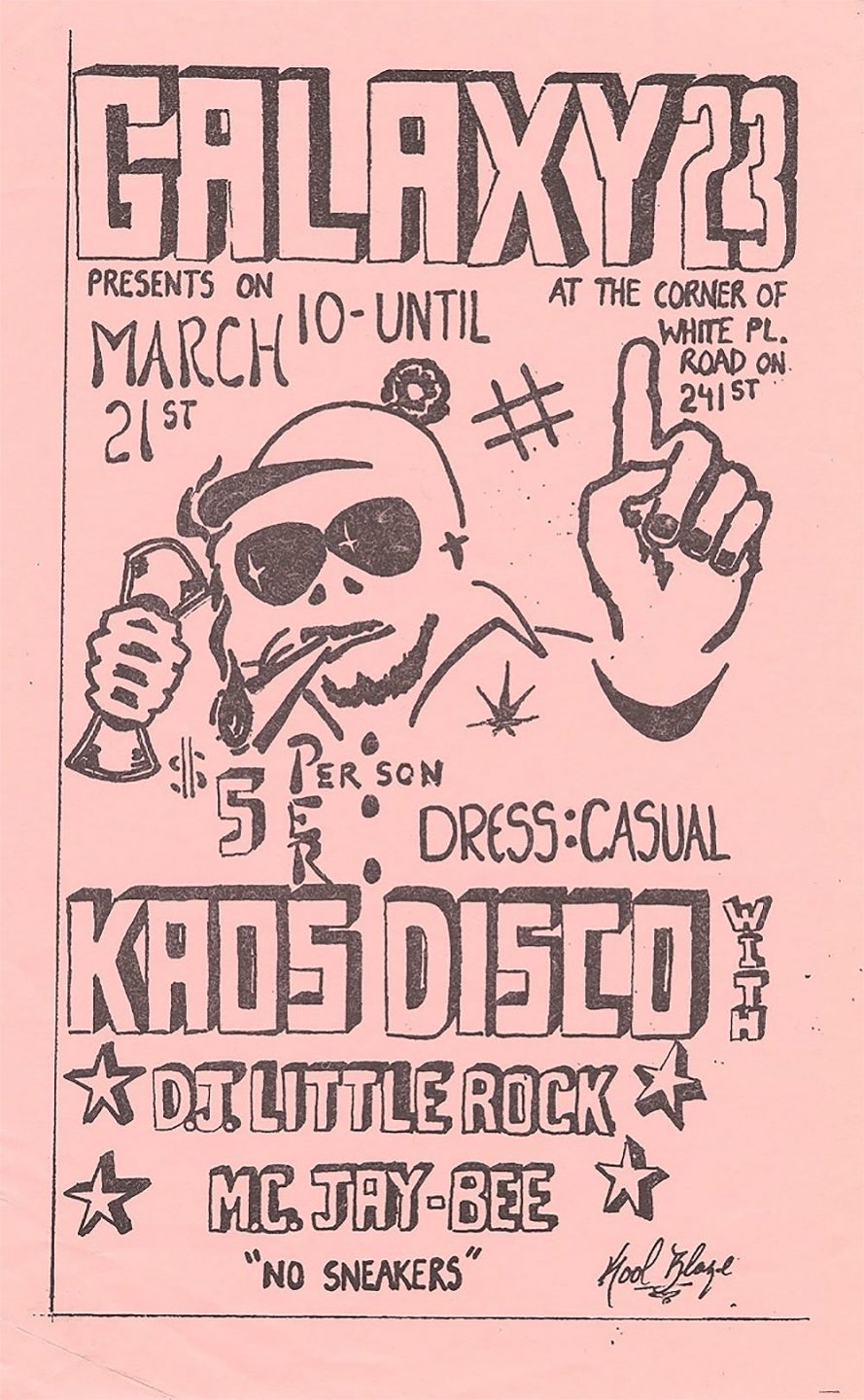

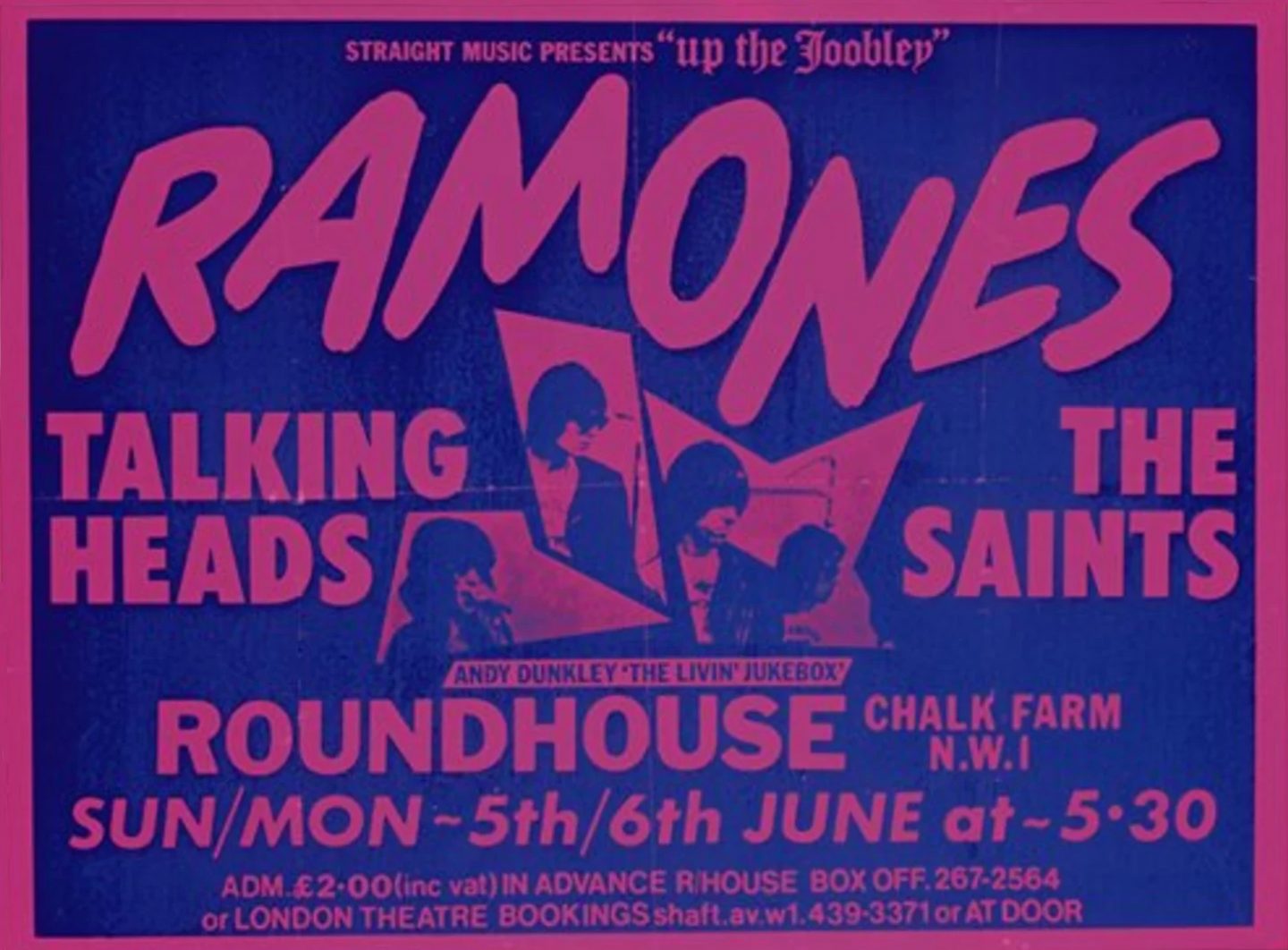

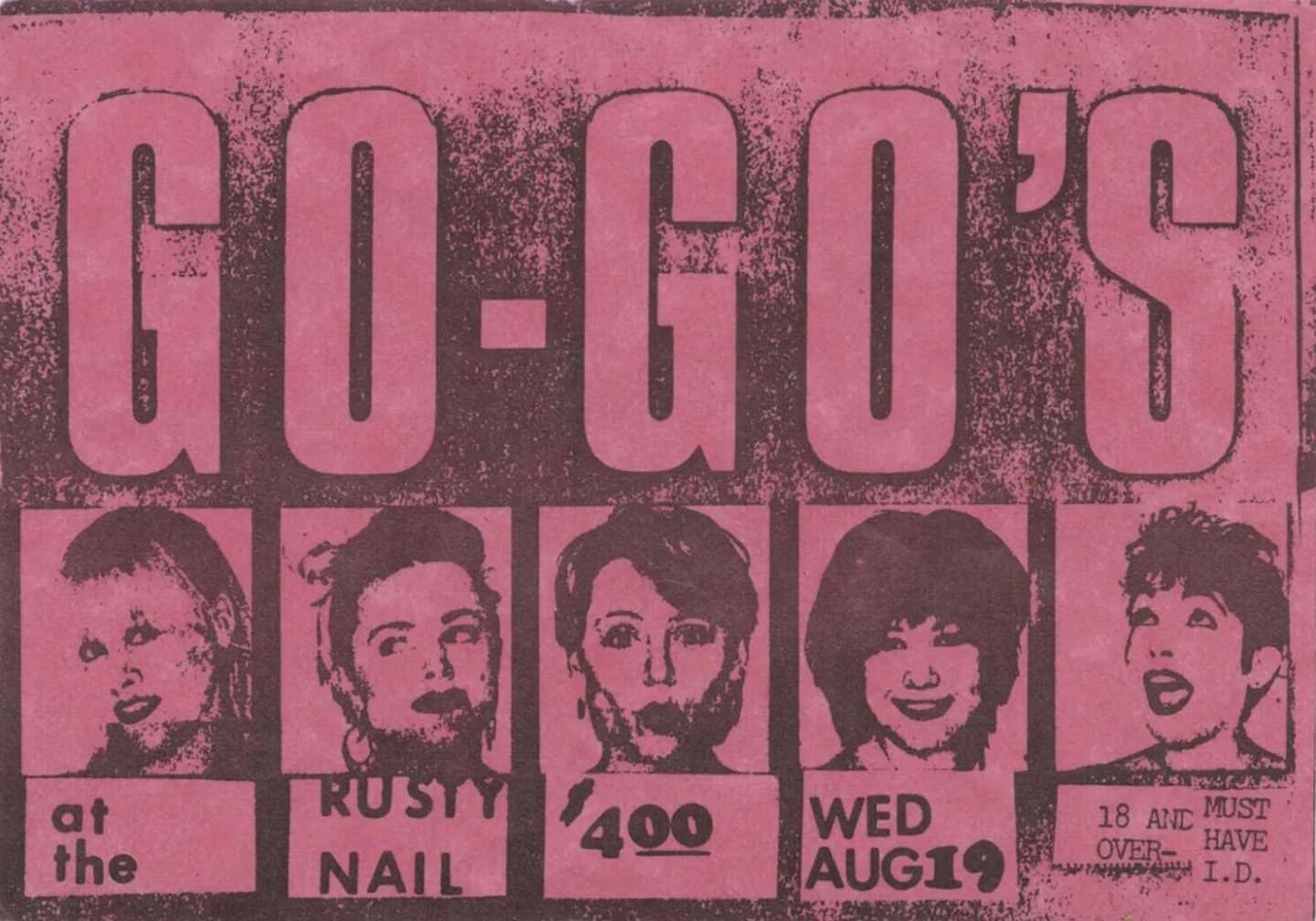

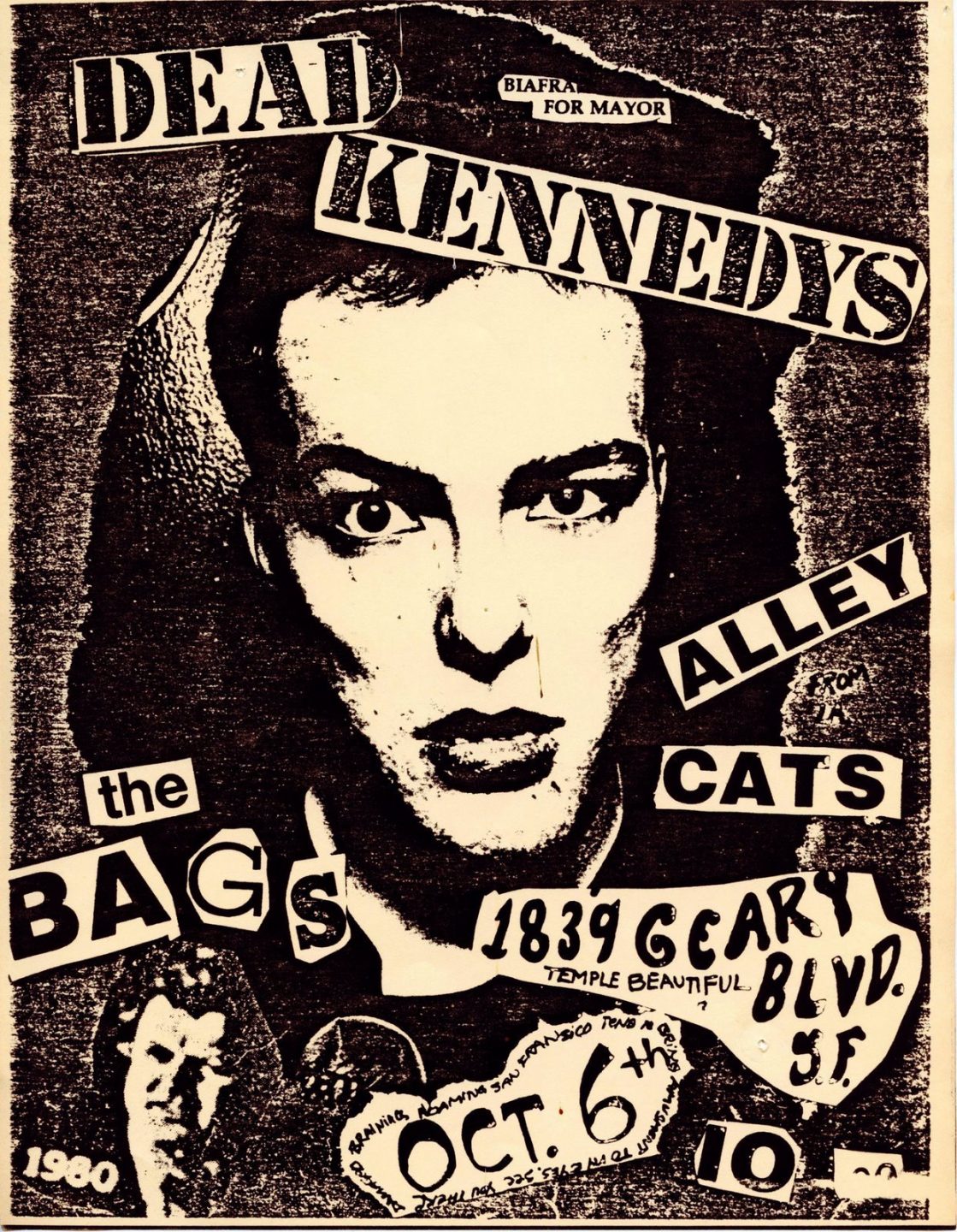

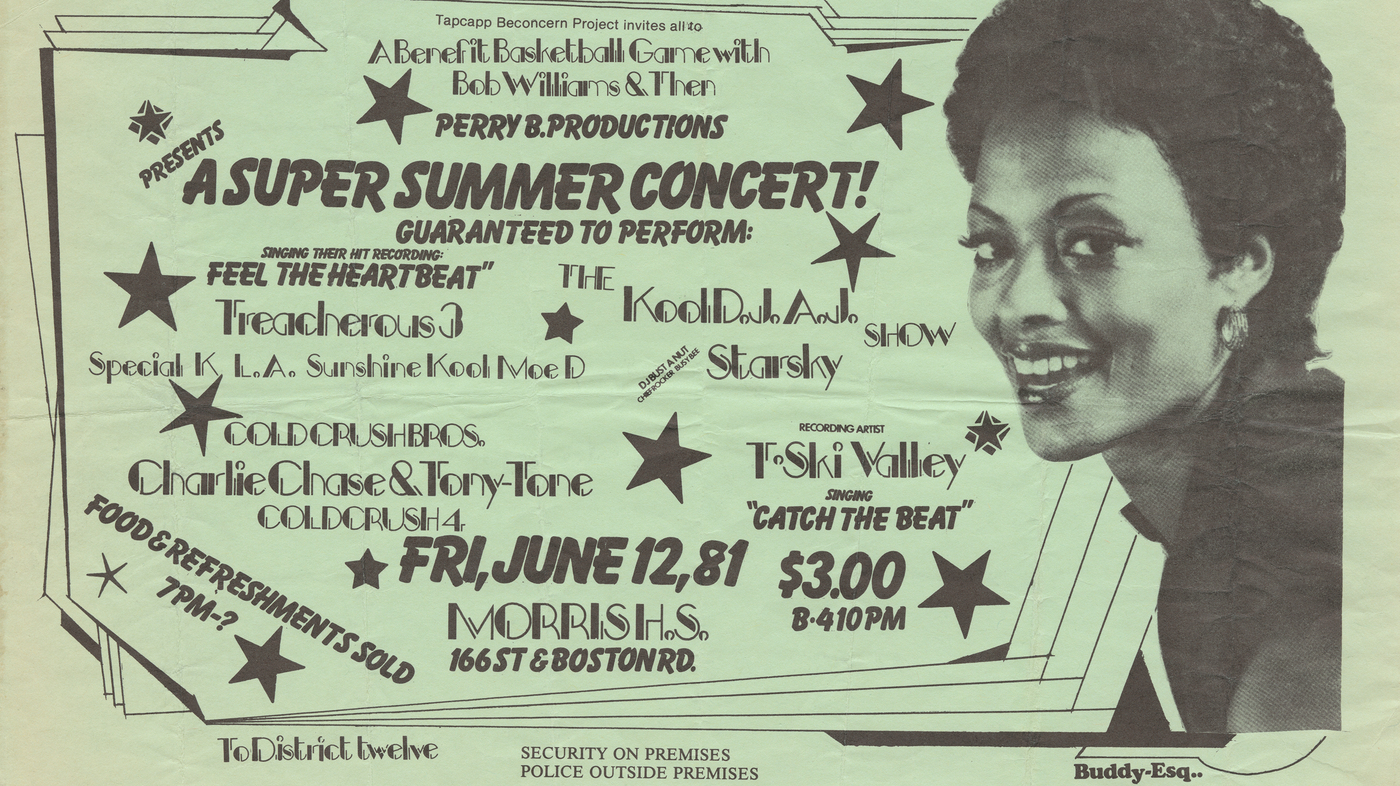

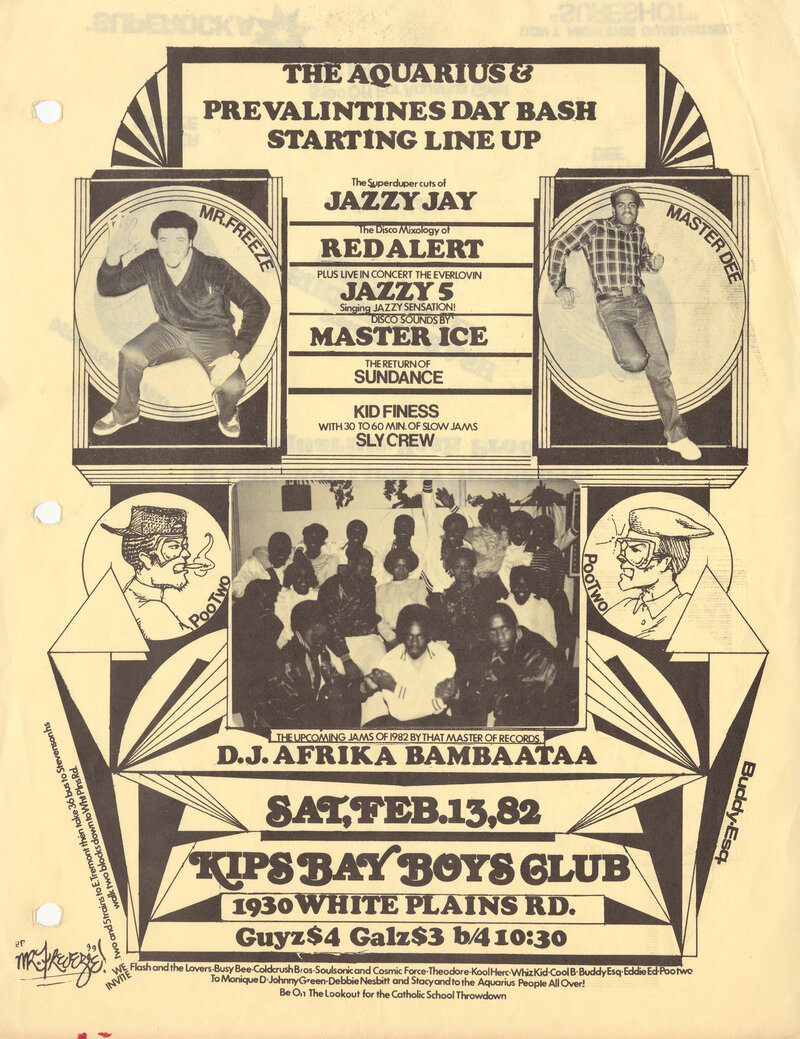

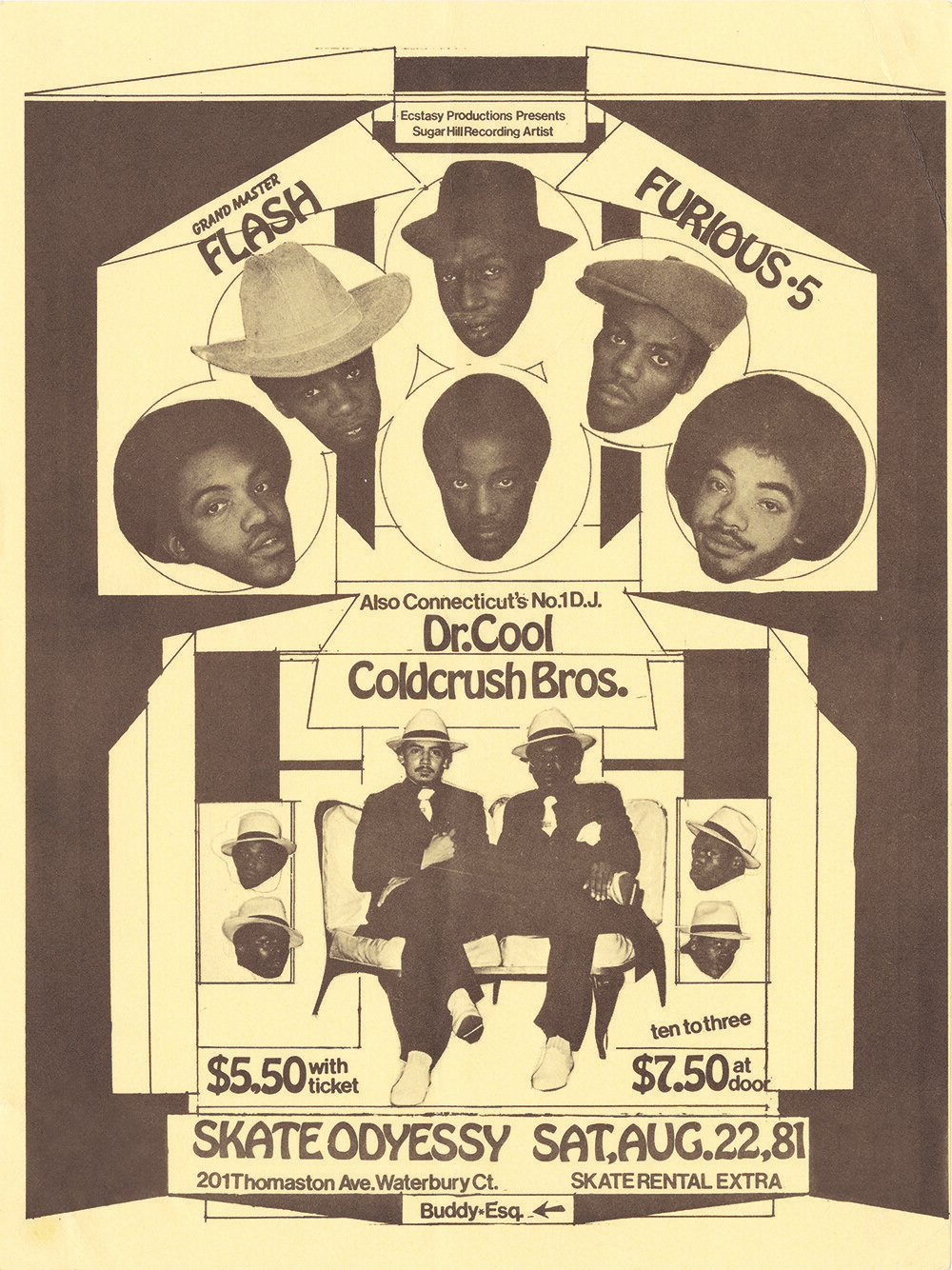

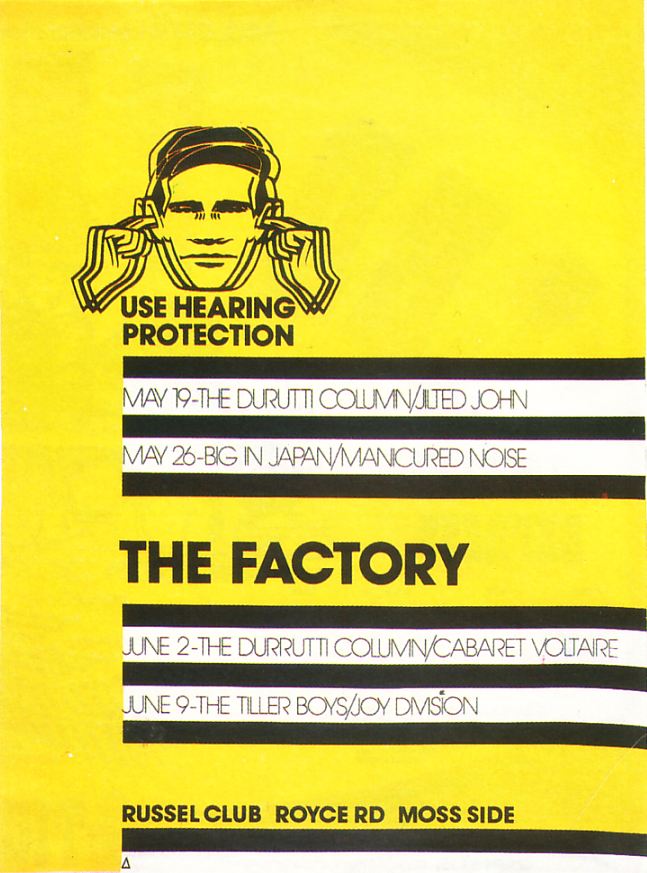

Out of this accessibility, the field of DIY marketing was born. Music, performance, and community building were essential aspects of cultural movements like punk, hip hop, and new wave that appeared in the seventies and eighties. Artists and designers tasked with promotion and marketing within these movements utilized new DIY technologies to create graphic works to advertise public programs and events. The new formats of xerox printing and rub-on, dry-transfer letters had their obvious limitations when compared to the process of offset lithography which, even today, stands as a dominant method within professional printing. Designers had to work solely in black and white and were limited to the type styles, weights, and sizes of dry-transfer letters that they could access or afford. Through these restraints came experimentation and visual innovation.

When surveying flyers and posters for punk and hip hop shows in the seventies and eighties you will see a mishmash of pop culture imagery, experimental typography, illustration, texture, pattern, and visual motifs that have no rationality or context. Many of the collaged compositions feature references to past periods and styles—art deco, art nouveau, constructivism, op art, even ancient roman art. The bricolage of DIY music and event marketing represents a stark contrast to the homogeneity of modernism which, by the end of the sixties, had become the style of the establishment.

These new DIY approaches were a significant factor in expanding the field of visual communication and, in turn, sparking the development of postmodernism which, by the eighties would become the accompanying visual vernacular of the arising digital era. Gone were the days of designers adhering to one dominant analogous style. Within postmodernism, there was space for multiple styles and approaches to coexist simultaneously. Modernism’s focus on rationality, function and minimalism is replaced by a practice centered on experimentation, self expression, and digital competency.

Buddy Esquire

One figure who exemplifies the creative innovation that came out of the new DIY formats of the seventies and eighties is the artist and designer Buddy Esquire. Referred to as the “king of hip-hop flyers” by his peers and admirers, Esquire’s work incorporates dynamic typography and graphic shapes within intricate, collaged compositions. Through his unique approach, he transforms the format of grassroots music marketing into an art form.

Largely self-trained Esquire developed a sense of design history through books that he would check out from his local library. He found inspiration in past movements like Art Deco and Constructivism, Esquire synthesized these approaches into a distinct, eye-catching style that became influential within the visual culture of hip-hop and beyond.

Peter Saville

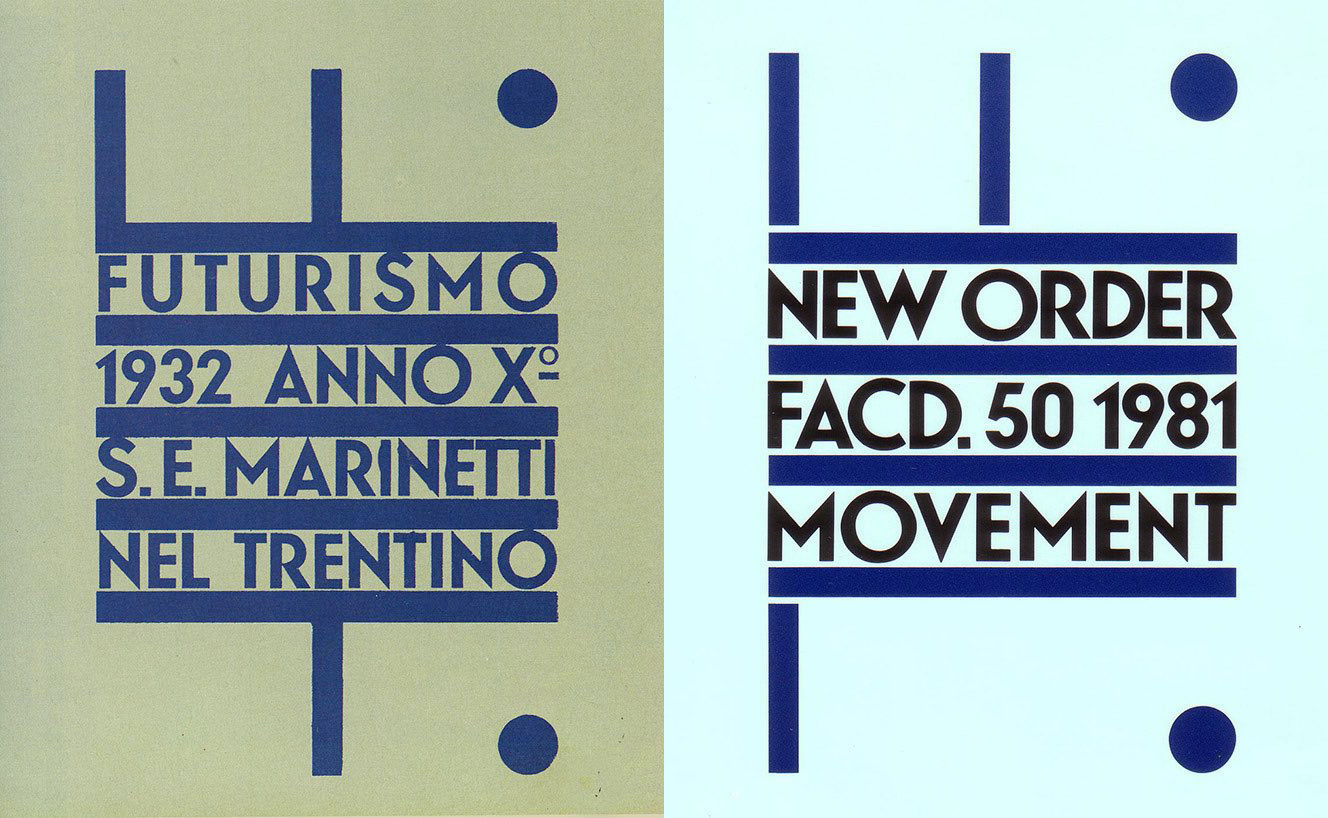

Another artist creating work for the music space in the seventies and eighties was London designer Peter Saville. Like Esquire, Saville was also mining past periods for design inspiration. He was particularly drawn to the early modernist movements like futurism, constructivism, and the work of German typographer Jan Tschichold who’s methodology represented a synthesis of Bauhaus graphic approaches. Saville’s references were often overt to the point of emulation. His cover design for the 1981 New Order album Movement was almost an identical recreation of futurist Fortunato Depero’s cover design for the publication Futurismo from 1932.

Saville designed for British record labels Factory Records and Dindisc where he created designs for such recognizable groups as Joy Division, Roxy Music, Wham, and Peter Gabriel. Later in his career he moved into advertising with a strong focus on fashion. He has created campaigns for iconic brands like Jil Sander, John Galliano, Yohji Yamamoto, and Raf Simons.

Paula Scher

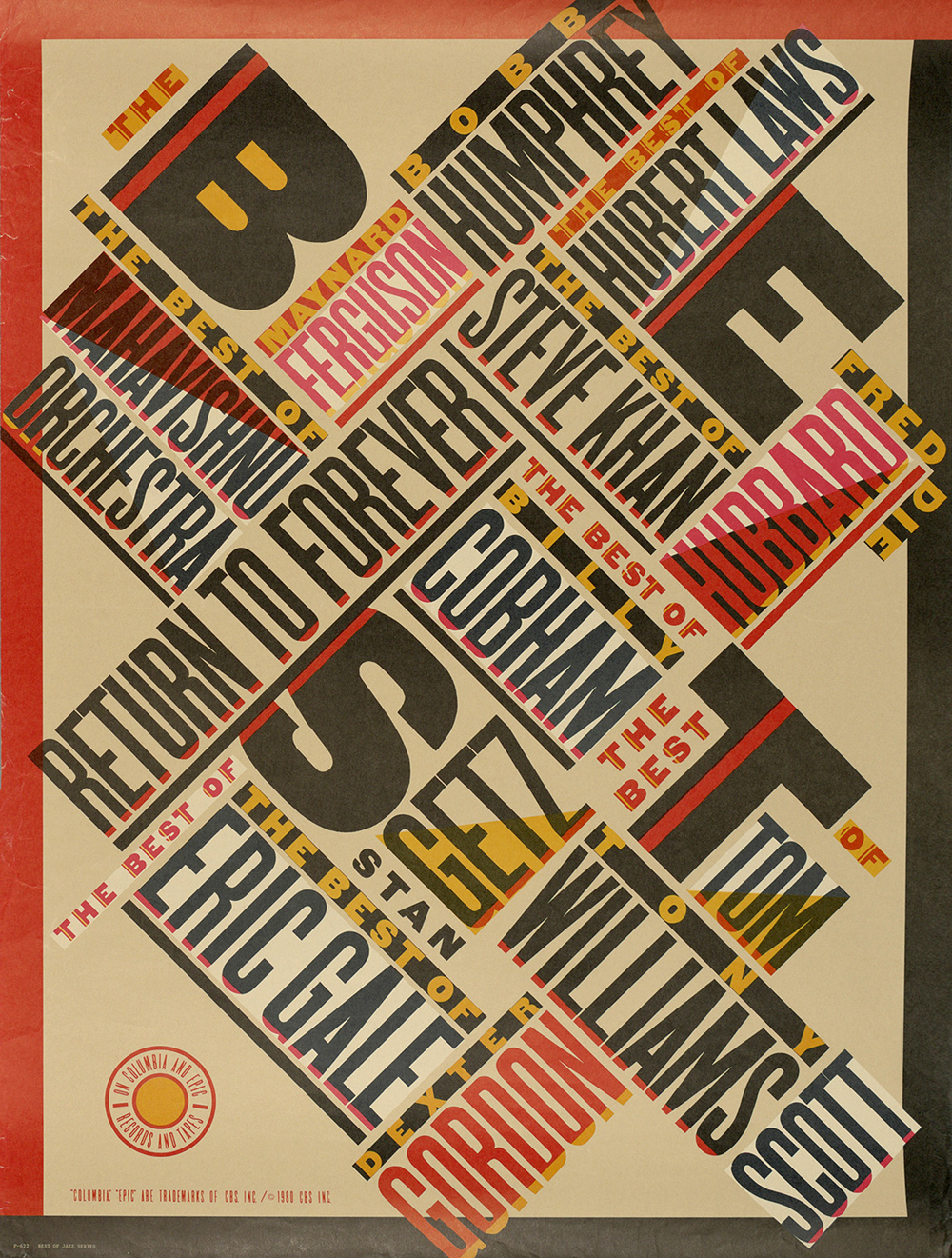

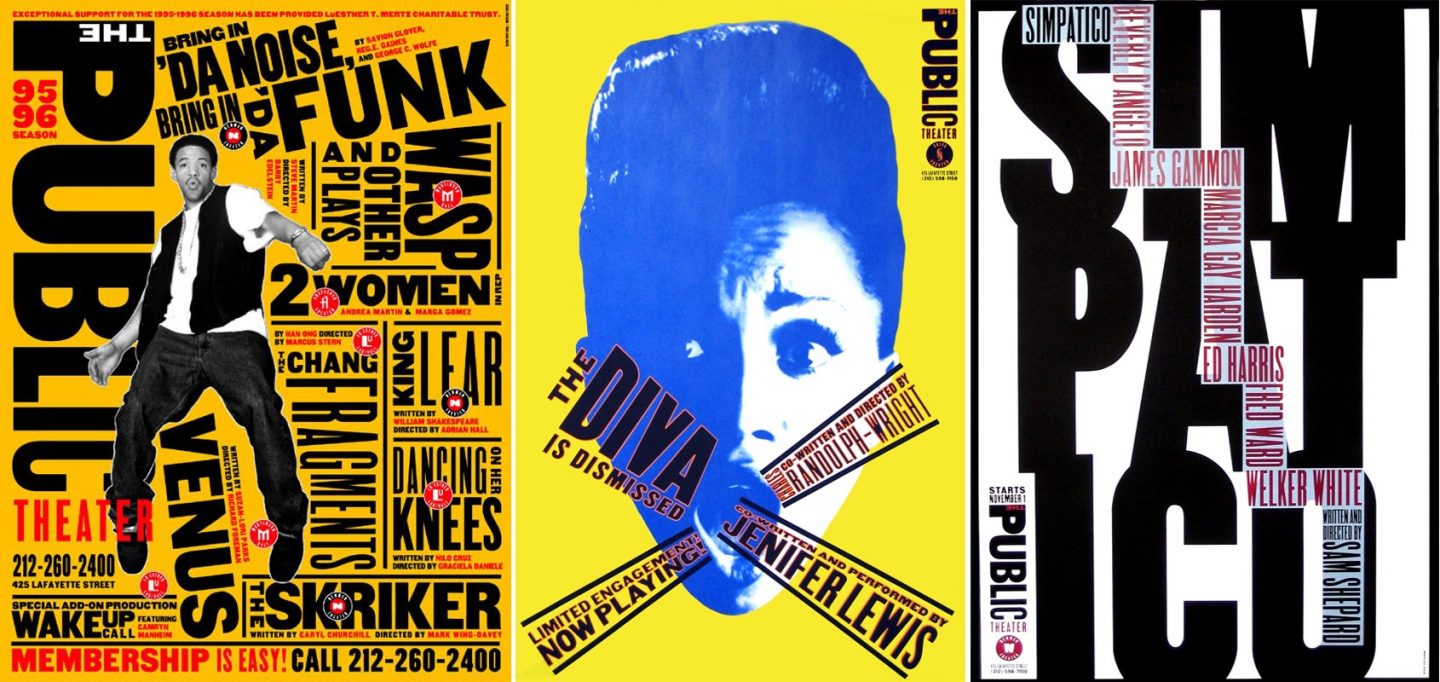

One of the most prominent designers to emerge from the early postmodern era is Paula Scher. Like Esquire and Saville, she also began her design career working in music, albeit in a more corporate context. For a decade she designed album covers— first for CBS records then for Atlantic. During this time, she experimented with multiple styles and approaches in the creation of record sleeve designs for a wide array of music artists.

Scher’s unique point of view stems from a vast knowledge of design history combined with a penchant for innovative experimentation. She continually references preceding eras and genres of design in her work.

In her “Best of Jazz” poster designed for the Smithsonian Institution in 1979, Scher incorporates a dynamic typographic approach which synthesizes the visual styles of early modernist movements—Futurism, the Bauhaus— with the graphic letterforms of wood type posters from the industrial revolution.

First released in 2015, Scher’s graphic identity for the Atlantic Theatre company evokes the stark minimalism of Russian Constructivism. The initial design system features a bold, wedge-like form paired with a vibrant tomato red. El Lissitzky’s iconic 1919 Constructivist work Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge comes to mind as an obvious inspiration for the brand system.

In another example—a 1984 advertisement for the Swiss watch brand Swatch—Scher reappropriates a travel poster designed fifty years earlier by the seminal Swiss modernist Herbert Matter. Plagiarism is part of the design strategy. By referencing Matter’s work, Scher is connecting Swatch to the well known legacy of Swiss design.

Since the nineties, Scher has been a working partner at Pentagram—one of the most celebrated design firms in the world. She continues to create iconic designs for globally renowned clients and has become one of the most recognizable personalities in the field of visual communication.